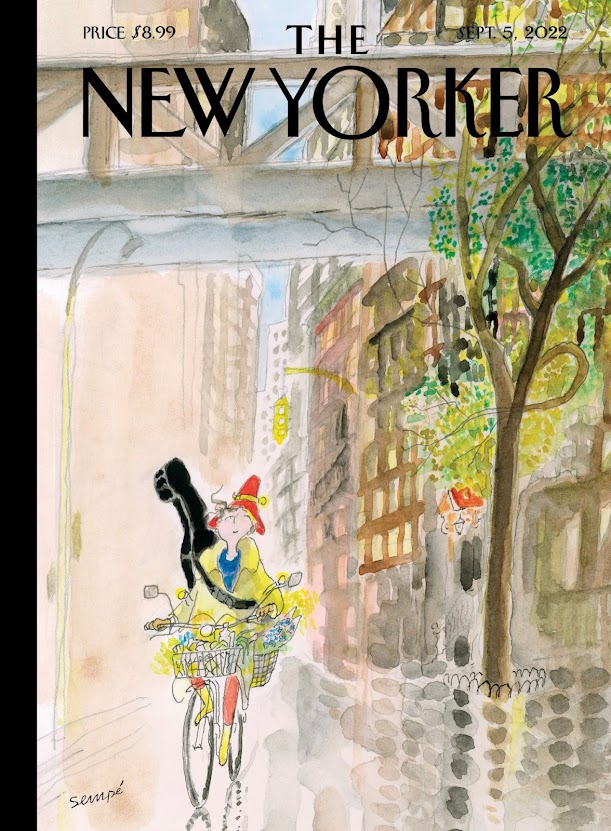

When Jean-Jacques Sempé, or J.J., as he was known in America, passed away on August 11th, at the age of eighty-nine, French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted, “[He] had the elegance to always remain light-hearted without ever missing a beat.” The tribute was one of many on both sides of the Atlantic; he was the rare Gallic artist beloved by Americans who managed never to lose his appeal in the eyes of his compatriots. The writer Charles McGrath once compared him to Brigitte Bardot, saying, “He’s a national institution who has acquired an almost universal appeal by remaining quintessentially French.” This week’s cover is Sempé’s hundred-and-fourteenth for the magazine, a monumental achievement. (Arthur Getz holds the record for most New Yorker covers, at two hundred and twelve.) I spoke to Martine Gossieaux, Sempé’s widow, about J.J.’s enduring love for the magazine.

What sort of impact did publishing his first New Yorker cover have on him?

I remember it vividly, because it came out two or three months after Jean-Jacques and I met, back in 1978. For him, it was something extraordinary. Before then, he had been doing black-and-white humor drawings. Now he had to think in color. He took up watercolor and was always searching for images that could make a good cover.

What was he looking for?

He searched for visual ideas that weren’t dependent on words. It was hard for him because, if, for example, he thought about painting a cat on a bed, he also had to come up with ways to show that the cat was in New York. He didn’t want to cheat by showing landmarks, so he had to distill how buildings, windows, and street lamps were specifically of the city.

Is the pedestrian passageway and the street lamp in the cover we’re publishing this week an example of this?

Yes, that image is the spirit of New York. He loved New Yorker covers, because he could choose his topic without limitations or impositions. He could paint a happy chicken in nature, for example. He loved that cover—it’s an extraordinary image because the subject is so mundane. He felt that he could embody the unique spirit of the magazine—the appreciation for quirky wit and humor shared by contributors and readers—in these images. It made him feel he was part of a family.

How did he discover The New Yorker?

He grew up in a small town near Bordeaux and didn’t have access to much culture as a young man. Then he went to present his drawings to the humorist Chaval. Chaval said, “O.K., this isn’t bad, but you should take a look at New Yorker covers.” They were a revelation for Jean-Jacques. He found elegance, wit—everything he loved—in those images. But he never sought The New Yorker out; it was almost as if he was waiting to be approached. Then the writer Jane Kramer met Jean-Jacques in Paris, and took an album of his drawings back to New York. That was how Jean-Jacques came to be published in the magazine.

I know he was delighted when I, a Frenchwoman, took over as the magazine’s art editor. What was J.J.’s relationship with William Shawn and the rest of the staff?

Jean-Jacques made a few trips to New York, where he mostly hung out with Jane Kramer, the cartoonist Ed Koren, and their friends. He went to Central Park and Brooklyn, and listened to jazz and concerts. Ed took Jean-Jacques to things [Ed] loved, like modern-dance performances. He lived in Vermont, so he also lent Jean-Jacques his office.

Language was sometimes an issue, as neither of us spoke English. When Lee Lorenz, the art editor at the time, spoke, he spoke so fast that I didn’t understand a word. But Jean-Jacques had a very musical ear. He nodded along and somehow seemed to get the gist of it. Also, many of the people we met were delighted to speak French, so we’d often go back home without having spoken or learned any English.

Who else did you meet at the New Yorker office?

Mr. Shawn had a meeting on Tuesdays with Lee Lorenz, where Lee would present the options for covers. There was no noise; all there was was the knowledge that Mr. Shawn was on the premises. Everyone stayed in his cubicle. I remember being in the lobby with Jean-Jacques, about to get into the elevator, when Mr. Shawn arrived. He nodded to us, we nodded back, and then he got into his elevator, next to ours, and went up. Mr. Shawn didn’t usually share his elevator. The atmosphere of reverence around him was quite amazing and strange. We’d wait in Ed’s office for Lee to come in and say that Mr. Shawn had accepted this or that drawing and what changes were requested.

What kind of changes?

Once Lee came back with a drawing, which had been accepted, of a cat perched on a bannister above a young girl, its tail giving her a mustache. Jean-Jacques was asked to remove the girl, which puzzled him because that was the joke. But he trusted Mr. Shawn, so he scratched her out with a razor blade—it’s not easy to make changes on a watercolor. When he looked at it, he felt Mr. Shawn was right; it was much better without the girl, without the obvious joke.

Did Jean-Jacques feel like he was representing France in the United States?

No, he didn’t feel he represented France or anything other than himself. But he was extremely proud of working with the magazine, of belonging to a group of artists that included people he admired very much, like Charles Addams or Saul Steinberg. For Jean-Jacques, to be published by a magazine that published Steinberg was a huge honor and a great privilege. He was always waiting to go from one New Yorker cover to the other. After the first one, that’s what guided him all his life.

No comments:

Post a Comment