From The Hollywood Reporter.

Did Andy Warhol violate copyright law when he based a portrait of Prince on a prominent photographer’s work?

That question was before the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday, as it grappled with the potentially massive consequences of a case that could change the landscape for art that’s created using other art.

Several justices observed the possible implications.

Several justices observed the possible implications.

“Why can’t we imagine that Hollywood can take a book and make a movie about it without paying?” Justice Clarence Thomas asked a lawyer for the Andy Warhol Foundation.

Justice Elena Kagan raised the opposite concern, mainly how a ruling against Warhol could chill artistic expression.

Justice Elena Kagan raised the opposite concern, mainly how a ruling against Warhol could chill artistic expression.

“The purpose of all copyright law is to foster creativity,” she said. “Why shouldn’t we ask if the thing we have here is new and entirely different.”

The justices often turned to ramifications in forms of art other than paintings and photographs.

They asked about figures who’ve relied on existing works to create new ones, including Peter Jackson, Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick.

On one side of the case is the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts.

On one side of the case is the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts.

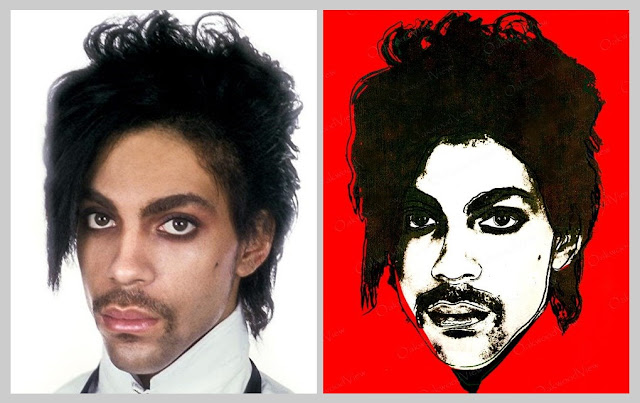

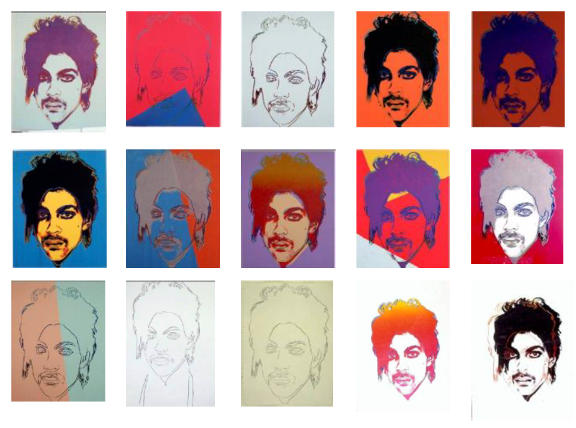

In 2017, it sued photographer Lynn Goldsmith seeking a court declaration that the artist’s 16-part Prince series doesn’t violate her copyright to the photo that underlays them.

Warhol had cropped and painted over Goldsmith’s images of Prince to make what the foundation’s lawyers argue are entirely new creations that comment on celebrity and consumerism.

The works have been displayed in museums, galleries and other distinguished public venues.

On the other side is Goldsmith, a prominent rock photographer who was hired by Newsweek in 1981 to take pictures of Prince.

Three years after the magazine ran the photo, Vanity Fair asked Warhol to create a portrait of Prince using Goldsmith’s photo as a template.

The artist’s series of 16 images, which the foundation now owns, have gone on to sell for six figures. When Prince died in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company Conde Nast ran a work from the series on the cover, for which Goldsmith received no money.

In 2019, a New York federal judge sided with Warhol that the Prince series qualifies as a new and distinct piece of art by incorporating a new meaning and message.

But a federal appeals court in 2021 disagreed.

During arguments on Wednesday, Roman Martinez, representing the Warhol Foundation, emphasized that the purpose and character of the artist’s work are entirely different than the photographs by Goldsmith.

Warhol intended to communicate the “dehumanizing impact of celebrity,” he said, whereas Goldsmith intended to celebrate Prince’s fame.

“There’s no dispute that the meaning of the works was different,” Martinez said. “This case is about whether that difference matters.”

Justice Samuel Alito inquired about how courts are supposed to determine the message of works of art.

“There’s no dispute that the meaning of the works was different,” Martinez said. “This case is about whether that difference matters.”

Justice Samuel Alito inquired about how courts are supposed to determine the message of works of art.

“Should it receive testimony by photographers and artists?” he asked. “Do you call art critics as experts?

Martinez replied that judges should do their own analysis using evidence from creators and experts, adding that they don’t necessarily need to determine the message but simply whether a new one could reasonably be perceived.

Martinez replied that judges should do their own analysis using evidence from creators and experts, adding that they don’t necessarily need to determine the message but simply whether a new one could reasonably be perceived.

He noted that the work should promote “creativity for the public good.”

“You make it sound so simple,” Alito responded. “There can be a lot of dispute.”

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. posed an analogy of an artist reproducing another artist’s work with the only difference being that the original is blue while the new work is yellow.

“You make it sound so simple,” Alito responded. “There can be a lot of dispute.”

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. posed an analogy of an artist reproducing another artist’s work with the only difference being that the original is blue while the new work is yellow.

If art critics testify that they send different messages, he asked, would the new work constitute fair use?

Martinez said “you’d have to listen to those critics” and independently “determine whether their analysis is reasonable.” When it comes to minor changes, “juries and fact finders can exercise common sense,” he said.

Martinez said “you’d have to listen to those critics” and independently “determine whether their analysis is reasonable.” When it comes to minor changes, “juries and fact finders can exercise common sense,” he said.

Regardless of the extent of changes, Lisa Blatt, a lawyer representing Goldsmith, stressed that there needs to be a justification for creating works using existing art.

The Warhol foundation never explained why it needed to use Goldsmith’s photographs when Warhol could’ve simply taken pictures of Prince himself, she argued.

“The petitioner responds that Warhol is a creative genius who imbued other people’s art with his own distinctive style,” she said.”But Spielberg did the same for film and [Jimmy] Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses.”

Alito indicated that Warhol sends a different message than Goldsmith about the “depersonalization of modern culture” in his works, a factor in fair use consideration.

“The petitioner responds that Warhol is a creative genius who imbued other people’s art with his own distinctive style,” she said.”But Spielberg did the same for film and [Jimmy] Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses.”

Alito indicated that Warhol sends a different message than Goldsmith about the “depersonalization of modern culture” in his works, a factor in fair use consideration.

Blatt responded that, by definition, derivative works add some new meaning to an existing work.

Yaira Dubin, a lawyer for the government arguing in support of Goldsmith, agreed that the changes in Warhol’s portraits are “ones that accompany adaptations of any work.”

Yaira Dubin, a lawyer for the government arguing in support of Goldsmith, agreed that the changes in Warhol’s portraits are “ones that accompany adaptations of any work.”

In enacting the copyright laws, Congress meant to protect original creators so that, for example, Hollywood doesn’t have free rein to adapt books into movies without licensing the rights from authors, she said.

Asked when fair use should apply, Dubin said relying on existing works for a new work should be limited to instances when it’s “necessary or at least useful.”

In total, the justices advanced more outwardly hostile queries to Martinez, the Warhol Foundation’s lawyer. He repeatedly faced questions and remarks about how to differentiate transformative and non-transformative derivatives if adding a new meaning is the most vital consideration to fair use.

Asked when fair use should apply, Dubin said relying on existing works for a new work should be limited to instances when it’s “necessary or at least useful.”

In total, the justices advanced more outwardly hostile queries to Martinez, the Warhol Foundation’s lawyer. He repeatedly faced questions and remarks about how to differentiate transformative and non-transformative derivatives if adding a new meaning is the most vital consideration to fair use.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett told him, “It seems to me like your meaning or messages test stretches the definition of transformation so broadly it eviscerates” the purpose and character analysis to determine the applicability of a fair use defense.

No comments:

Post a Comment