James Sturm writes about his experiences drawing and submitting cartoons to The New Yorker.

It was a Tuesday in July and I was sitting in the "cartoonist lounge" on the 20th floor of the Condé Nast building in Times Square with an envelope containing 10 drawings: my first cartoon submissions to The New Yorker. Every Tuesday is judgment day, the day Robert Mankoff, the magazine's cartoon editor, meets with cartoonists face to face.Another seven or eight cartoonists were squeezed into the small waiting room, which is dominated by a long coffee table stacked with hundreds of New Yorker magazines. A giant print of a Sam Gross cartoon hung on one wall; underneath was a couch. Sam Gross sat on the couch. The other cartoonists either tried to engage in awkward small talk or just kept silent. Sam, by far the oldest and most established cartoonist in the cramped space, held court. He said, "Dr. Seuss was not a good artist. He couldn't draw kids. They were just adults with big heads."

It was a Tuesday in July and I was sitting in the "cartoonist lounge" on the 20th floor of the Condé Nast building in Times Square with an envelope containing 10 drawings: my first cartoon submissions to The New Yorker. Every Tuesday is judgment day, the day Robert Mankoff, the magazine's cartoon editor, meets with cartoonists face to face.Another seven or eight cartoonists were squeezed into the small waiting room, which is dominated by a long coffee table stacked with hundreds of New Yorker magazines. A giant print of a Sam Gross cartoon hung on one wall; underneath was a couch. Sam Gross sat on the couch. The other cartoonists either tried to engage in awkward small talk or just kept silent. Sam, by far the oldest and most established cartoonist in the cramped space, held court. He said, "Dr. Seuss was not a good artist. He couldn't draw kids. They were just adults with big heads."

One by one, in the order they'd arrived, cartoonists disappeared into Mankoff's office and emerged a few minutes later. One cartoonist was asked by another "How'd you do?" The reply was a shrug. Everyone's expectations were low, and how could they not be? Rejection is the norm.

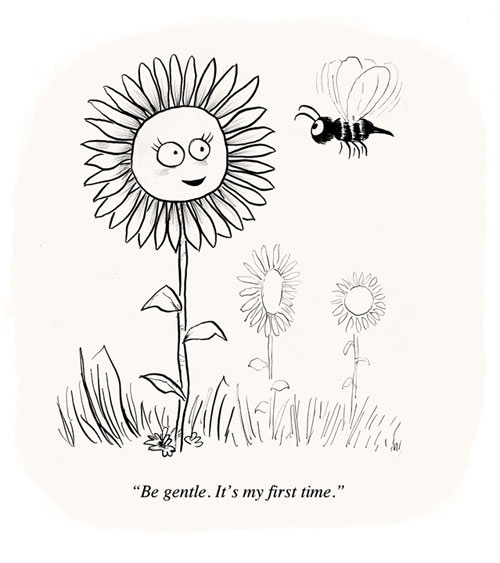

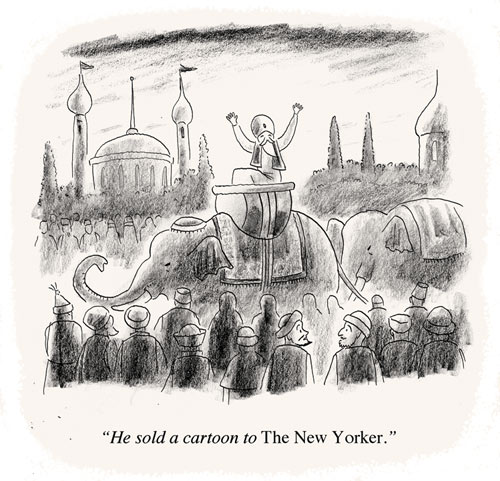

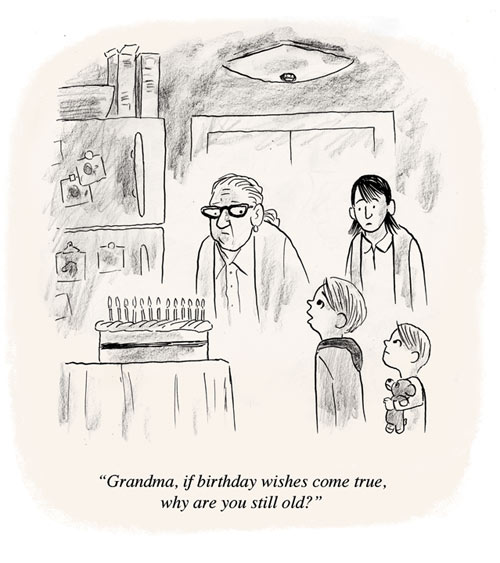

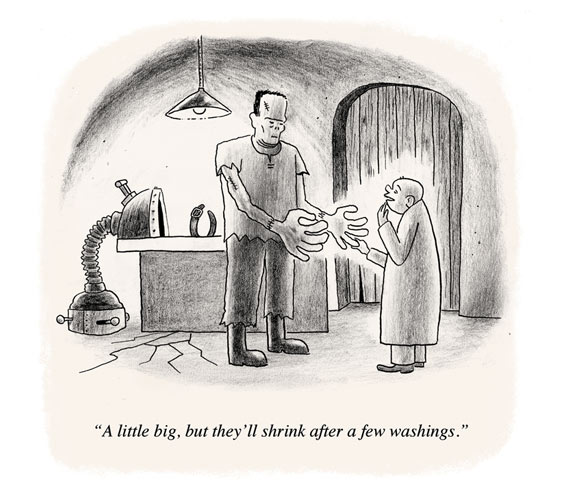

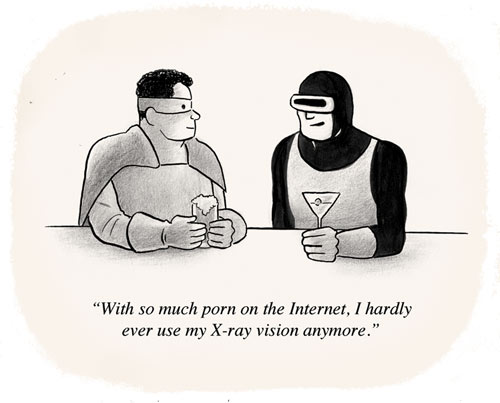

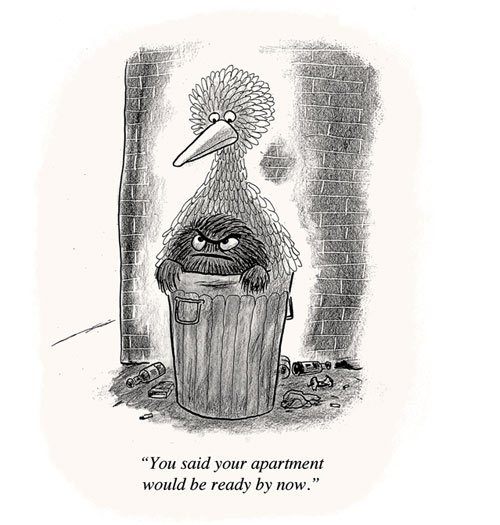

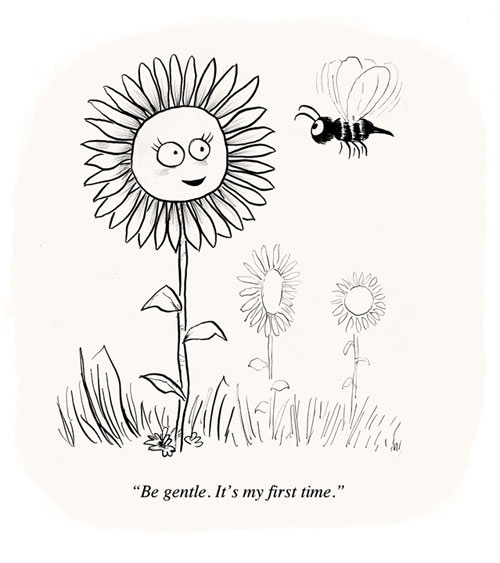

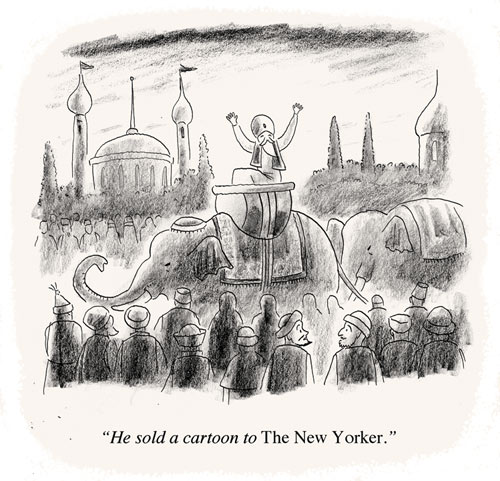

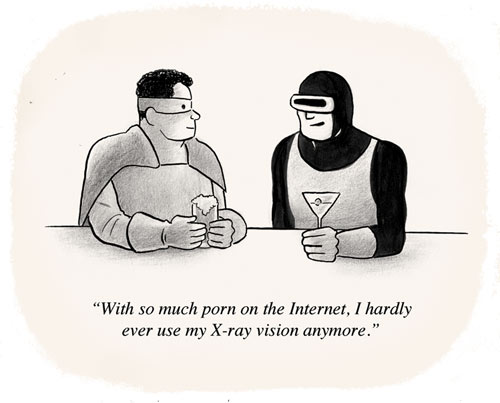

Fifty years ago, you could make a modest living selling work to popular, general interest magazines like Cavalier, Fact, Look, the Saturday Evening Post, and the Saturday Review, but today it's almost impossible to eke out a living as a gag cartoonist. There are still places that buy gag cartoons (like pharmaceutical brochures and yoga magazines) but none with the tradition or cachet of The New Yorker.I don't normally draw gag cartoons; I'm what's now called a "graphic novelist." I'm not really considering a career change, but I was dealing with the mid-career blahs and wanted to try something new. It takes me several years to write and draw a book. The book's subject determines and limits what I can and can't draw. I enjoy the process, but it's a slog. I wanted more spontaneity in my creative life. So in March I decided to fill a sketchbook, 90 pages, withNew Yorker-style cartoons—one cartoon a day for three months. No excuses.If making graphic novels felt like a staid long-term relationship, then doing gag comics is like playing the field. One day I could draw a fortuneteller; the next, an astronaut. I went from sultans to superheroes, robots to rabbits. I felt liberated. I refused to get bogged down or fuss over the drawings. I spent no more than an hour with any one cartoon, and many took far less time than that. For the first two weeks I was feeling my oats. I already had a half-dozen keepers and was confident there were plenty more winners on the way. It was at this point that I started dreaming of actually selling a cartoon to The New Yorker.

Fifty years ago, you could make a modest living selling work to popular, general interest magazines like Cavalier, Fact, Look, the Saturday Evening Post, and the Saturday Review, but today it's almost impossible to eke out a living as a gag cartoonist. There are still places that buy gag cartoons (like pharmaceutical brochures and yoga magazines) but none with the tradition or cachet of The New Yorker.I don't normally draw gag cartoons; I'm what's now called a "graphic novelist." I'm not really considering a career change, but I was dealing with the mid-career blahs and wanted to try something new. It takes me several years to write and draw a book. The book's subject determines and limits what I can and can't draw. I enjoy the process, but it's a slog. I wanted more spontaneity in my creative life. So in March I decided to fill a sketchbook, 90 pages, withNew Yorker-style cartoons—one cartoon a day for three months. No excuses.If making graphic novels felt like a staid long-term relationship, then doing gag comics is like playing the field. One day I could draw a fortuneteller; the next, an astronaut. I went from sultans to superheroes, robots to rabbits. I felt liberated. I refused to get bogged down or fuss over the drawings. I spent no more than an hour with any one cartoon, and many took far less time than that. For the first two weeks I was feeling my oats. I already had a half-dozen keepers and was confident there were plenty more winners on the way. It was at this point that I started dreaming of actually selling a cartoon to The New Yorker.

Once upon a time, before The New Yorker featured photos and illustrations, the cartoon was the magazines' visual star. The cartoon took up, and deserved, more real estate on the page. The art was built to last. Drawings boasted delicately controlled gray washes, accomplished pen and brushwork, and finely observed details. You got the idea that the cartoonists paid attention as they moved through the city; their drawings existed in the observable world as much as in the realm of ideas. In addition to his diagrammatic drawings of time and space, Saul Steinberg could render Fifth Avenue or the interior of a theater with a flourish of details that testified to his presence. The charming yet limited range of a James Thurber drawing stood out as an exception.I'm not sure Thurber would stand out in today's New Yorker. Mankoff's cartooning credo, as outlined in his 2002 book, The Naked Cartoonist, is that it's the idea that transforms a quirky little drawing into a New Yorker cartoon. Or as Mankoff writes, "It's not the ink, it's the think." As a result, today's New Yorker cartoons reflect Mankoff's own work—a more narrow, idiosyncratic style that, like Thurber's, inspires readers like me to think, "I could do that."

Once upon a time, before The New Yorker featured photos and illustrations, the cartoon was the magazines' visual star. The cartoon took up, and deserved, more real estate on the page. The art was built to last. Drawings boasted delicately controlled gray washes, accomplished pen and brushwork, and finely observed details. You got the idea that the cartoonists paid attention as they moved through the city; their drawings existed in the observable world as much as in the realm of ideas. In addition to his diagrammatic drawings of time and space, Saul Steinberg could render Fifth Avenue or the interior of a theater with a flourish of details that testified to his presence. The charming yet limited range of a James Thurber drawing stood out as an exception.I'm not sure Thurber would stand out in today's New Yorker. Mankoff's cartooning credo, as outlined in his 2002 book, The Naked Cartoonist, is that it's the idea that transforms a quirky little drawing into a New Yorker cartoon. Or as Mankoff writes, "It's not the ink, it's the think." As a result, today's New Yorker cartoons reflect Mankoff's own work—a more narrow, idiosyncratic style that, like Thurber's, inspires readers like me to think, "I could do that."

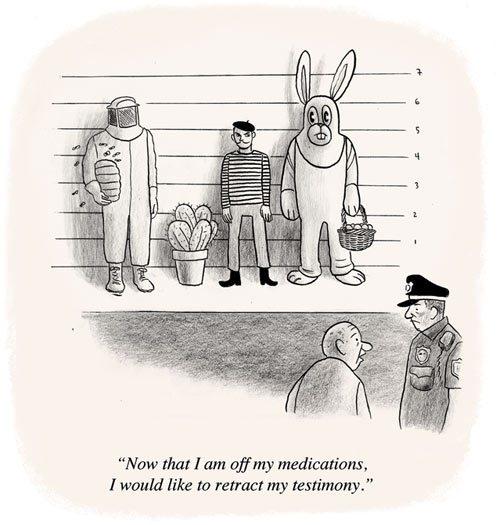

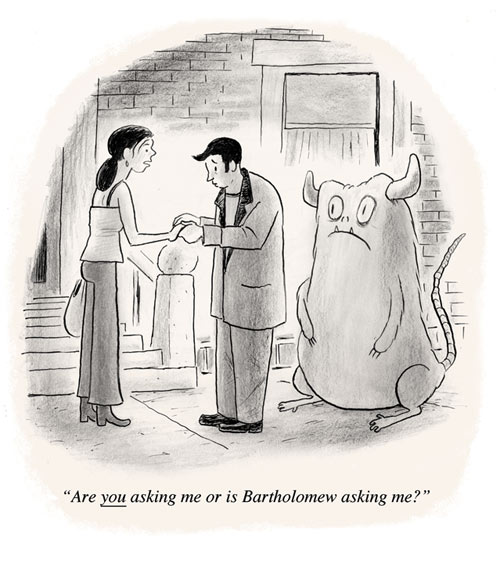

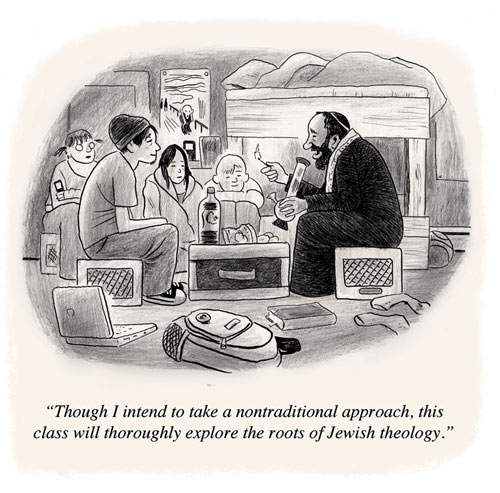

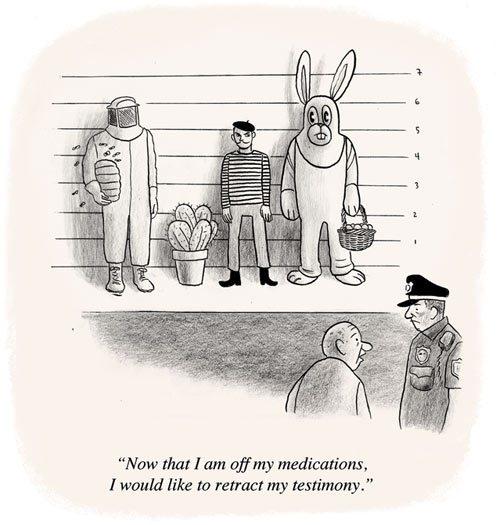

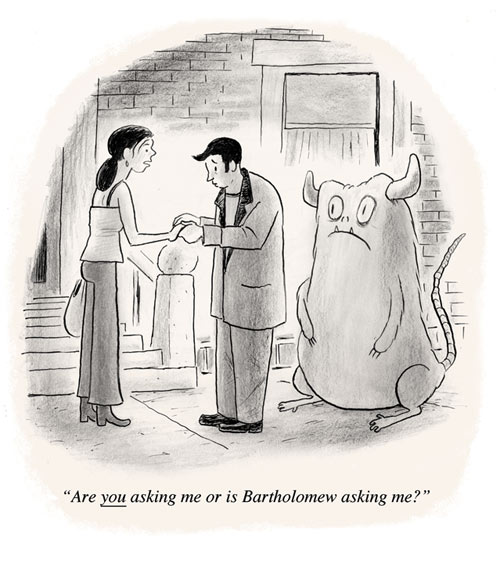

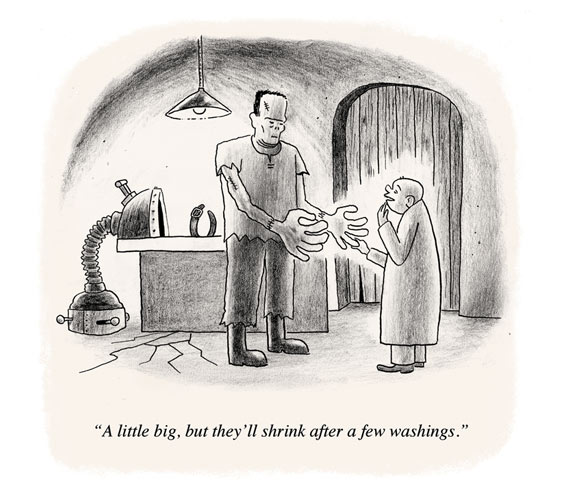

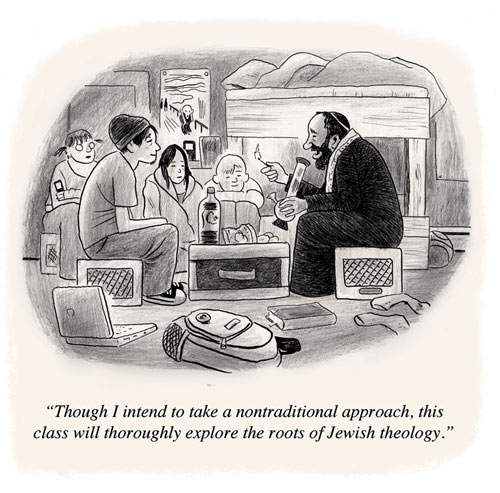

By my fourth week of daily drawing, I hit a wall. It got harder and harder to generate gags, and I often found myself staring at a blank page at eleven o'clock at night, just wanting to get something down so I could go to bed. My measuring stick was the great New Yorker cartoonist William Steig. Besides knowing what made people tick, Steig possessed that holy combination of looseness and precision that gives great cartooning its casual authority. I knew I could never compare with Steig, but I didn't want to embarrass myself, either. I had my pride, and if I was going to produce another 60 gags I needed to approach things differently.I started doodling randomly on scrap sheets of papers, trying to draw something surprising or something that made me laugh. The best of these doodles— Frankenstein's monster staring at his big hands, a rabbi taking bong hits in a dorm room—I would then redraw slightly tighter in the gag sketchbook and have faith a caption would come later. If after a week I couldn't come up with anything, I'd e-mail the drawing to my dad, who, by virtue of entering The New Yorker caption contest on a regular basis (and once being one of the three finalists), seemed the right man for the job.I wondered whether this was cheating, somehow, but dismissed the notion. Though today's New Yorker cartoonists write their own gags, throughout the magazine's first four decades, most cartoonists didn't (Steinberg and Steig being the most notable exceptions). Even many of the magazine's most iconic cartoons, Charles Addams' skier (the tracks on either side of the tree), Thurber's decapitated fencer ("touché"), and almost everything Peter Arno drew were written by someone else.

By my fourth week of daily drawing, I hit a wall. It got harder and harder to generate gags, and I often found myself staring at a blank page at eleven o'clock at night, just wanting to get something down so I could go to bed. My measuring stick was the great New Yorker cartoonist William Steig. Besides knowing what made people tick, Steig possessed that holy combination of looseness and precision that gives great cartooning its casual authority. I knew I could never compare with Steig, but I didn't want to embarrass myself, either. I had my pride, and if I was going to produce another 60 gags I needed to approach things differently.I started doodling randomly on scrap sheets of papers, trying to draw something surprising or something that made me laugh. The best of these doodles— Frankenstein's monster staring at his big hands, a rabbi taking bong hits in a dorm room—I would then redraw slightly tighter in the gag sketchbook and have faith a caption would come later. If after a week I couldn't come up with anything, I'd e-mail the drawing to my dad, who, by virtue of entering The New Yorker caption contest on a regular basis (and once being one of the three finalists), seemed the right man for the job.I wondered whether this was cheating, somehow, but dismissed the notion. Though today's New Yorker cartoonists write their own gags, throughout the magazine's first four decades, most cartoonists didn't (Steinberg and Steig being the most notable exceptions). Even many of the magazine's most iconic cartoons, Charles Addams' skier (the tracks on either side of the tree), Thurber's decapitated fencer ("touché"), and almost everything Peter Arno drew were written by someone else.

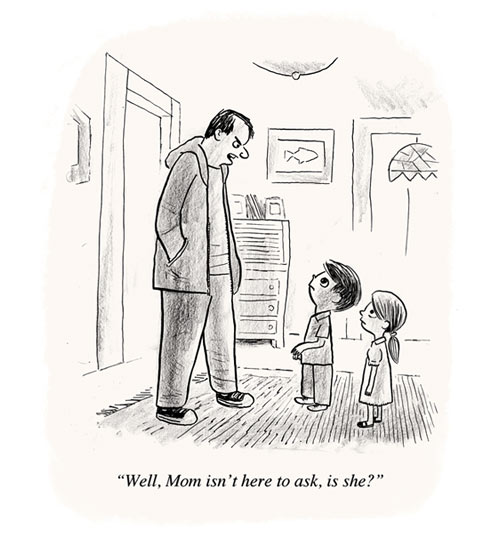

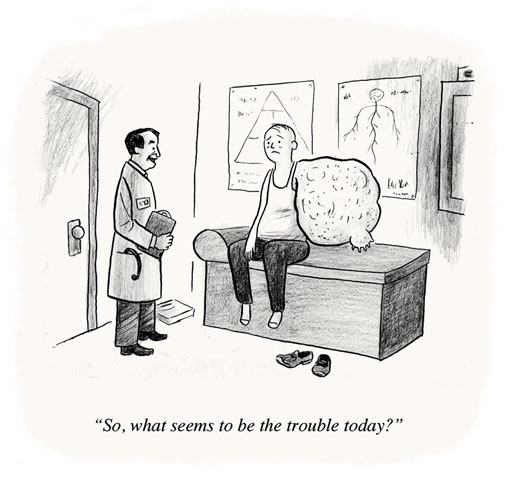

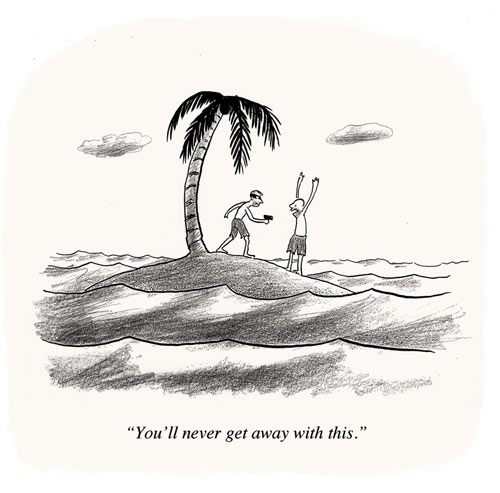

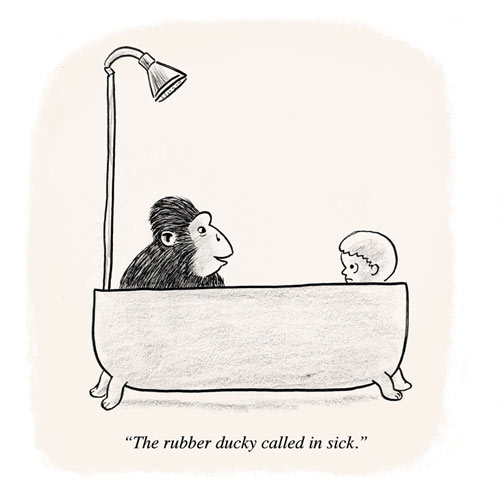

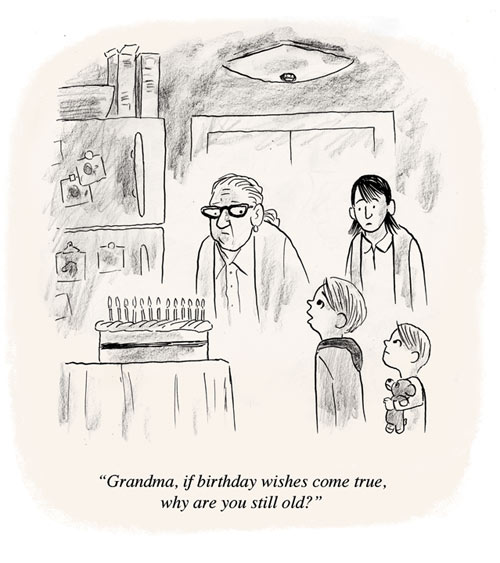

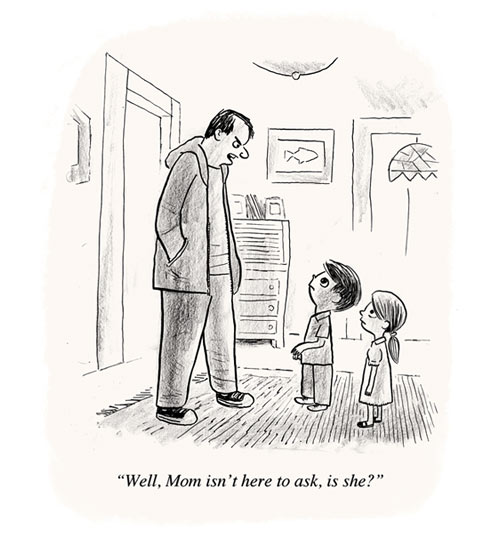

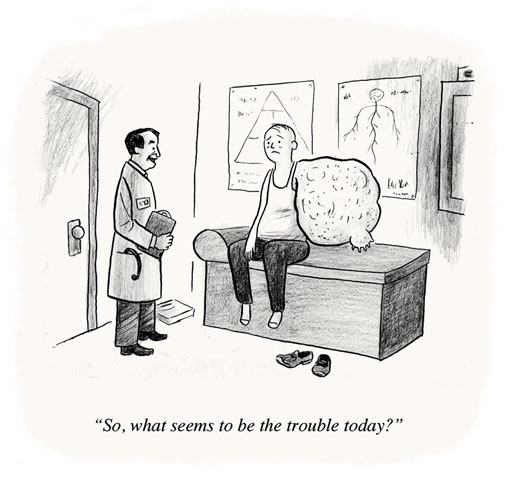

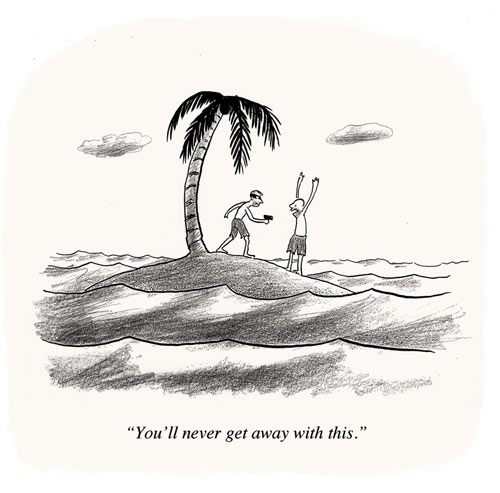

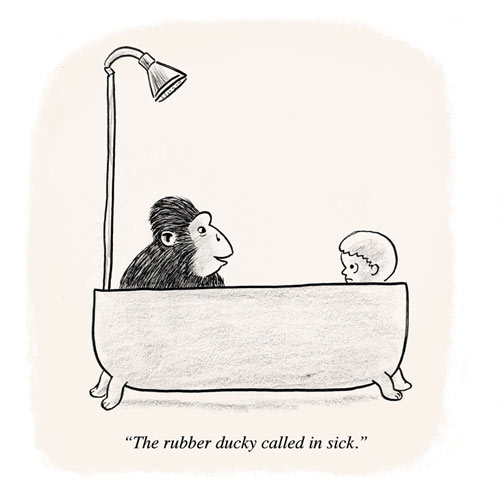

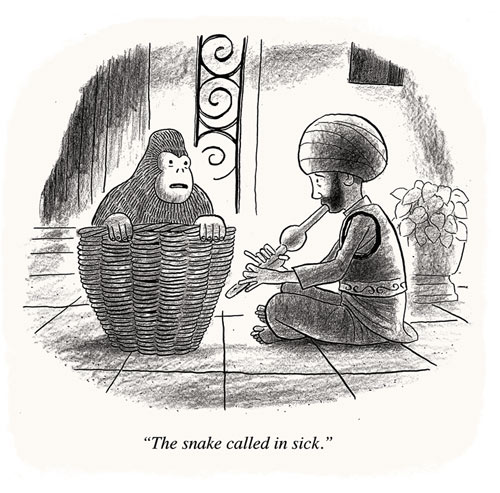

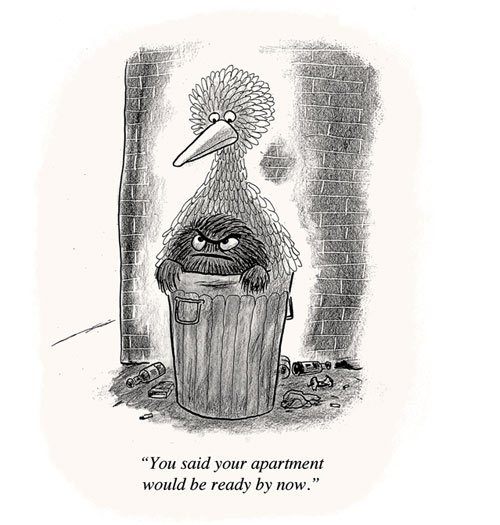

Still, what had been taking me an hour a day now seemed like it was taking over my life. I always had a pen ready and whether I was hanging out with my kids, going to the doctor (after a suspicious looking bull's-eye rash appeared on my chest), or bickering with my wife—I was filtering it for a potential cartoon. I had to extract from any given situation some larger cultural observation. Or some statement about the human condition. Or something that resembled cleverness. My life has always felt as if it was grist for my creative mill, but now the mill had a daily quota that I was straining to meet.When my life didn't offer usable material I started reaching for the low hanging fruit: desert-island gags and gorillas.

Still, what had been taking me an hour a day now seemed like it was taking over my life. I always had a pen ready and whether I was hanging out with my kids, going to the doctor (after a suspicious looking bull's-eye rash appeared on my chest), or bickering with my wife—I was filtering it for a potential cartoon. I had to extract from any given situation some larger cultural observation. Or some statement about the human condition. Or something that resembled cleverness. My life has always felt as if it was grist for my creative mill, but now the mill had a daily quota that I was straining to meet.When my life didn't offer usable material I started reaching for the low hanging fruit: desert-island gags and gorillas.

According to Matthew Diffee's book of unpublished New Yorker cartoons, The Rejection Collection, there are about 50 regular New Yorker cartoonists who submit 10 cartoons each week. That's 500 cartoons vying for about 12 to 20 slots. That's not counting submissions from cartoonists whose work appears in the magazine irregularly or the thousand or so weekly unsolicited submissions (which stand almost no chance of getting in).When I finished my sketchbook I estimated about 50 of my 90 comics wouldn't look out of place in the current issue of The New Yorker (a generous assessment). Fortitude is one of the qualities Mankoff is looking for in a cartoonist. With about 50 cartoons, I could submit a batch of 10 for five weeks. Since Mankoff often wants to see people submit for months (if not years) before buying a cartoon, this didn't afford me a huge window of opportunity, but years ago, against all odds, I sold a cover to the magazine on my first try and I was hoping lightning could strike twice.From reading cartoonist's blogs and books about The New Yorker's history I knew that the cartoon editor looked at work on Tuesdays. My friend Harry Bliss (New Yorker cartoonist and fellow Vermonter) was kind enough to put me in touch with Mankoff's assistant, who told me to show up on July 12 so Mankoff could look at my work.On the Tuesday I showed up there were three cartoonists besides me who were hoping to make a first sale. Two had been showing up for more than six months, the other one for several years. Clearly, no one is in this for the money. If you make a sale, depending on your tenure with the magazine, you can make anywhere from around $675 to $1,400 a gag. Seems like a lot for a little drawing, but the dues you pay are steep.The ones who have sold hundreds of cartoons over decades can bring in an additional $300-$1,000/month from reprints via the Cartoon Bank. But even with this additional income, you probably need to have a lot more gigs or a day job.

According to Matthew Diffee's book of unpublished New Yorker cartoons, The Rejection Collection, there are about 50 regular New Yorker cartoonists who submit 10 cartoons each week. That's 500 cartoons vying for about 12 to 20 slots. That's not counting submissions from cartoonists whose work appears in the magazine irregularly or the thousand or so weekly unsolicited submissions (which stand almost no chance of getting in).When I finished my sketchbook I estimated about 50 of my 90 comics wouldn't look out of place in the current issue of The New Yorker (a generous assessment). Fortitude is one of the qualities Mankoff is looking for in a cartoonist. With about 50 cartoons, I could submit a batch of 10 for five weeks. Since Mankoff often wants to see people submit for months (if not years) before buying a cartoon, this didn't afford me a huge window of opportunity, but years ago, against all odds, I sold a cover to the magazine on my first try and I was hoping lightning could strike twice.From reading cartoonist's blogs and books about The New Yorker's history I knew that the cartoon editor looked at work on Tuesdays. My friend Harry Bliss (New Yorker cartoonist and fellow Vermonter) was kind enough to put me in touch with Mankoff's assistant, who told me to show up on July 12 so Mankoff could look at my work.On the Tuesday I showed up there were three cartoonists besides me who were hoping to make a first sale. Two had been showing up for more than six months, the other one for several years. Clearly, no one is in this for the money. If you make a sale, depending on your tenure with the magazine, you can make anywhere from around $675 to $1,400 a gag. Seems like a lot for a little drawing, but the dues you pay are steep.The ones who have sold hundreds of cartoons over decades can bring in an additional $300-$1,000/month from reprints via the Cartoon Bank. But even with this additional income, you probably need to have a lot more gigs or a day job.

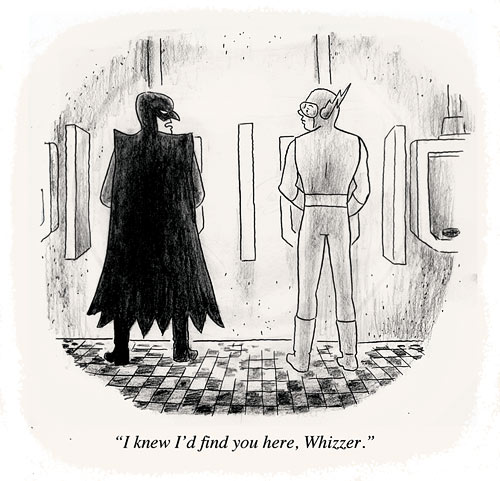

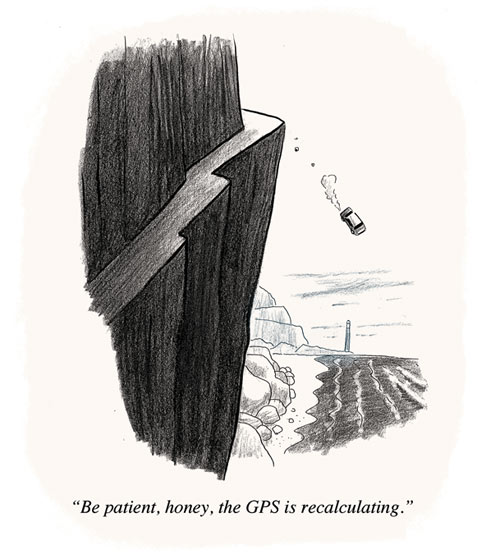

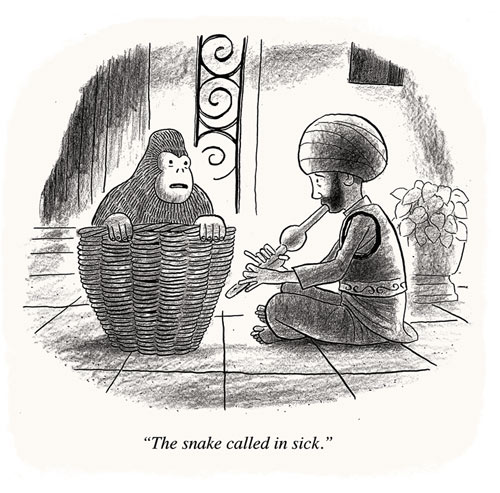

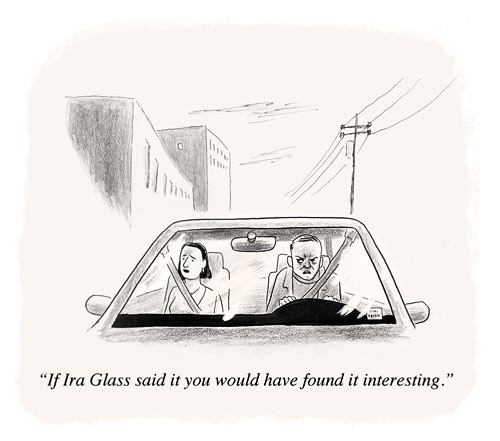

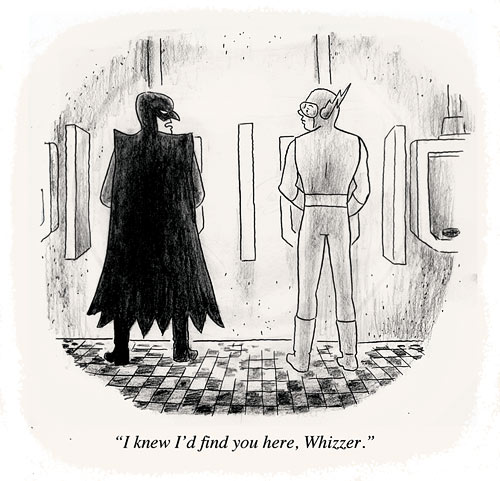

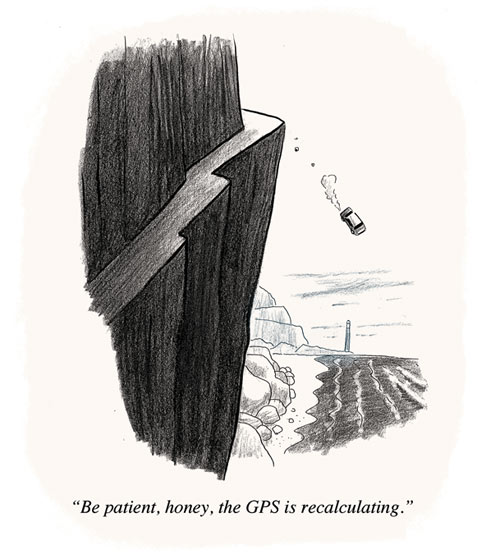

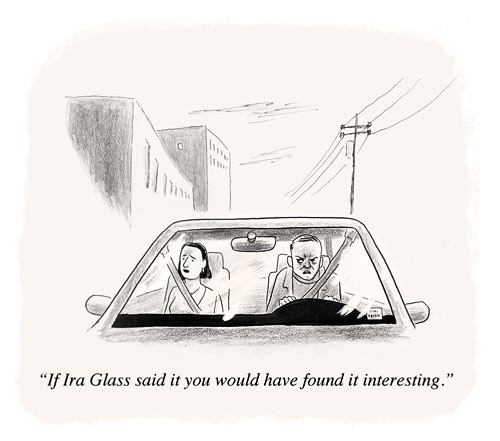

Mankoff greeted me cordially, and I handed him my 10 cartoons. He read each of them in front of me. He told me I can draw and he'd like to see more people in the magazine who can draw. Promising.He thought that a superhero gag would be funnier if I used specific superheroes (huh) and that the mention of Ira Glass in a caption would be too obscure (really?). Mankoff thought that the complaint in my GPS gag was already dated (not for my GPS!) and that my gorilla cartoon with the snake charmer might be deemed offensive or just passé (point taken).He suggested I stay away from desert-island gags and the incongruity gag (in which there's a disconnect between the caption and the picture). These are overdone, and if he were going to use this type of material, he would turn to the all-stars he already has on his bench (baseball metaphor his).

Mankoff greeted me cordially, and I handed him my 10 cartoons. He read each of them in front of me. He told me I can draw and he'd like to see more people in the magazine who can draw. Promising.He thought that a superhero gag would be funnier if I used specific superheroes (huh) and that the mention of Ira Glass in a caption would be too obscure (really?). Mankoff thought that the complaint in my GPS gag was already dated (not for my GPS!) and that my gorilla cartoon with the snake charmer might be deemed offensive or just passé (point taken).He suggested I stay away from desert-island gags and the incongruity gag (in which there's a disconnect between the caption and the picture). These are overdone, and if he were going to use this type of material, he would turn to the all-stars he already has on his bench (baseball metaphor his).

Mankoff put two of my cartoons aside to consider for the next issue's final cut. I knew they wouldn't sell; I saw this as a small gesture of encouragement. The rest he handed back to me. He explained how hard it was to get into the magazine and that he wasn't just looking for a good cartoon but someone who could be a "New Yorker cartoonist."Mankoff said so many submissions he looks at are not even in the neighborhood and that I was in the neighborhood but that I was going to have to figure out what my work was about, how it was distinct. I had to decide what would make it exceptional. He told me to keep submitting via e-mail each week.

Mankoff put two of my cartoons aside to consider for the next issue's final cut. I knew they wouldn't sell; I saw this as a small gesture of encouragement. The rest he handed back to me. He explained how hard it was to get into the magazine and that he wasn't just looking for a good cartoon but someone who could be a "New Yorker cartoonist."Mankoff said so many submissions he looks at are not even in the neighborhood and that I was in the neighborhood but that I was going to have to figure out what my work was about, how it was distinct. I had to decide what would make it exceptional. He told me to keep submitting via e-mail each week. My audience had lasted 12 minutes. Many of the other cartoonists who had already shown work were still there, waiting to go out for lunch—a long-standing Tuesday tradition that any cartoonist, published or not, could be part of.On the way to the restaurant, we passed giant banners of Charles Addams drawings hanging from the facade of the the Lunt Fontanne Theater. I wondered whether any of today's New Yorker cartoonists were exceptional enough to someday inspire a Broadway musical.At the restaurant a long table was already set up and glasses of red wine were served as soon as we took our seat. The conversation was more relaxed than at the office. I sat next to David Sipress, one of my favorite current New Yorker cartoonists, who told me he submitted for 25 years before he cracked the pages of The New Yorker. "If you are a gag cartoonist and after a while you are not in The New Yorker," he said, "you begin to feel like a failure."I didn't feel like a failure, but, listening to Sipress, I did suddenly feel like a fraud. This wasn't where I belonged as a cartoonist, and if by some miracle I were able to sell one of my 50 cartoons, I would be taking a slot away from someone more deserving. There would be no more submissions. I had already wasted enough of everyone's time.I started the drawings for the right reasons, but in taking them to The New Yorker, I was looking for a feather for my cap. Mankoff was right: There wasn't anything unique and distinct about my gag work. I was in the neighborhood, just visiting, not willing to stay there long enough to become a full-time resident.At the end of the meal, each of us gave Sam Gross 20 bucks and headed our separate ways. I got my car out the garage and headed back to Vermont. My affair was over, and I was ready to go home.

My audience had lasted 12 minutes. Many of the other cartoonists who had already shown work were still there, waiting to go out for lunch—a long-standing Tuesday tradition that any cartoonist, published or not, could be part of.On the way to the restaurant, we passed giant banners of Charles Addams drawings hanging from the facade of the the Lunt Fontanne Theater. I wondered whether any of today's New Yorker cartoonists were exceptional enough to someday inspire a Broadway musical.At the restaurant a long table was already set up and glasses of red wine were served as soon as we took our seat. The conversation was more relaxed than at the office. I sat next to David Sipress, one of my favorite current New Yorker cartoonists, who told me he submitted for 25 years before he cracked the pages of The New Yorker. "If you are a gag cartoonist and after a while you are not in The New Yorker," he said, "you begin to feel like a failure."I didn't feel like a failure, but, listening to Sipress, I did suddenly feel like a fraud. This wasn't where I belonged as a cartoonist, and if by some miracle I were able to sell one of my 50 cartoons, I would be taking a slot away from someone more deserving. There would be no more submissions. I had already wasted enough of everyone's time.I started the drawings for the right reasons, but in taking them to The New Yorker, I was looking for a feather for my cap. Mankoff was right: There wasn't anything unique and distinct about my gag work. I was in the neighborhood, just visiting, not willing to stay there long enough to become a full-time resident.At the end of the meal, each of us gave Sam Gross 20 bucks and headed our separate ways. I got my car out the garage and headed back to Vermont. My affair was over, and I was ready to go home. *

*

One by one, in the order they'd arrived, cartoonists disappeared into Mankoff's office and emerged a few minutes later. One cartoonist was asked by another "How'd you do?" The reply was a shrug. Everyone's expectations were low, and how could they not be? Rejection is the norm.

No comments:

Post a Comment