|

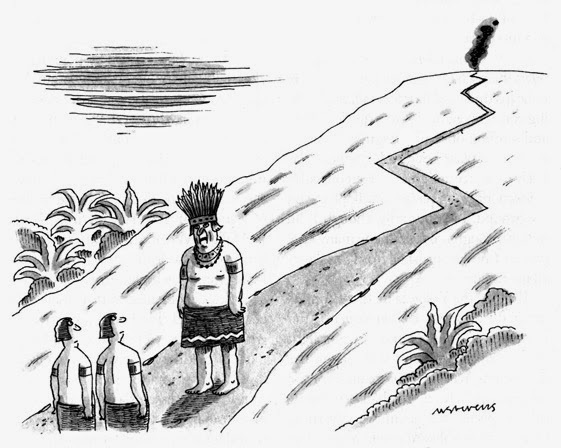

| "Any requests, babe, before I call it a night?" |

|

| "You really think this will work?" |

I understand that before you made it in the New Yorker, you were working on breaking into the underground comix scene. Can you tell us more about this part of your journey?

I tried a number of things when I started out: cartoon strips (two ideas almost made the big time, but eventually died a lonely, undeserved death), greeting card designs, and animation — did a couple of short things for Sesame Street, also, back in the day. I was living in San Francisco at the time, which was a hotbed of underground cartooning. Naturally, I gave it a shot, but my efforts were mostly only seen in my own little neighborhood newsletter, which I ran with a friend of mine.

I had a day job at Rolling Stone magazine then, and every once in a while would do illustrations for some of their stories. I also did work for an alternative newspaper called the The Bay Area Guardian and collaborated on a couple of books written by Charles Monegan, including one called Poodles From Hell, which I understand now has a tiny cult following. Eventually, I decided I was somewhere between underground and above-ground, and went back to trying to sell to mainstream magazines.

The single-panel comic is a hard sell as a form of income-producing work these days. Why do you think this is? Do you feel the form will adapt to the comedic needs of a new age?

It’s never been easy to make a living as a magazine cartoonist. Harder now that the web has usurped print to the point it has (and will to do in the future). Publishing on the Internet is much different. We’re paid much less, for one thing. The Net eats the work up and spits it back out through social media and in other ways, usually without further compensation for the artist. It’s easier to get your work seen, but harder to get paid.

|

| "I know what I said ten minutes ago. That was the old me talking." |

Further, what do you think is the future of cartoons at the New Yorker? Will these carry on indefinitely into the future?

Readers still look for them, sometimes before reading the rest of the magazine, and it’s impossible to imagine the New Yorker without its cartoons. There is the other side of publication, of course, the New Yorker Daily Cartoon, for example, which only appears online. There may be more of that sort of thing.

How many cartoons do you draw a week? How many roughs do you do for a final piece? And how many ideas do you throw out per one you keep?

I do ten or so rough ideas a week. Usually, my roughs are very close to finished work, so when I make a sale, I make any needed changes and draw up a finish using the light-table. I probably throw out 90% of the ideas or semi-ideas I do each week. Some I hold onto for later perusal. Ideas look different at different times. Many times, a doodle done a few days or weeks earlier will look better after I see it again. It may just need a slightly different caption or detail in the drawing to bring it to life.

|

| "The gods want olive oil, but it has to be virgin olive oil." |

Whose work inside and outside of the New Yorker do you respect the most (barring yours of course)?

I pretty much admire all of the cartoonists in the magazine, past and present. Sam Gross is one of my favorites. I consider him a “cartoonist’s cartoonist.” For a while, when I first moved to New York from California, some of us would gather at his apartment for cartooning “jam-sessions.” I got good advice from him and the other established cartoonists there. One thing Sam said, especially, stands out in my memory: “Never throw anything away.” He was right. There are times when those old ideas and sketches come in handy. Sam’s still at it and I still love his work.

Another cartoonist I’ve always loved, although didn’t see him personally too often, was Charles Barsotti, who just recently passed away. Nobody could say so much with a few lines of drawing.

If you could give advice to your twenty-something self just starting out, what would it be? What about some twenty-something cartoonist today?

I’m not sure what I’d say to my twenty-year-old self. We’re actually still in touch, but all he seems to want to do is drink beer. I’d tell him that maybe he should consider some lifestyle changes, maybe work a little harder and party a little less. If only he’d listen!

No comments:

Post a Comment