One of the first female cartoonists to succeed in a male-dominated field, Trina Robbins somehow also found time to make clothes for Mama Cass and show up in a Joni Mitchell song.

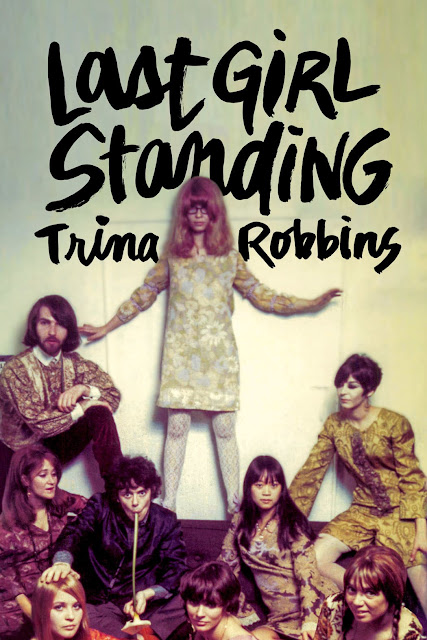

In her new memoir, Last Girl Standing, groundbreaking cartoonist Trina Robbins tells stories about her brushes with fame that include making clothes for Mama Cass and Donovan, hanging out with the Byrds, sleeping with Jim Morrison, and appearing in the Joni Mitchell song “Ladies of the Canyon”: “Trina wears her wampum beads” and “her coat’s a secondhand one, trimmed in antique luxury.”

She also writes about growing up in Brooklyn, with a family she describes as functional rather than dysfunctional.

Her father had Parkinson’s and couldn’t work, so her mother supported the family of four by working as a second-grade teacher.

They didn’t have tons of money, Robbins said, but her parents made sure she and her sister felt loved.

In the book, she tells the story of walking with her father from their house in South Ozone Park to the newly opened Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy) to watch the planes land and take off and singing all the way home.

“I got so much love,” the 79-year-old artist said. “I never hugged more people.”

Wearing a blue sweater and blue nail polish, Robbins seemed outgoing and chatty.

A graphic artist from the get go, Robbins even in childhood loved cartoons, along with science fiction and fantasy books such as Lord of the Rings.

“This is going to sound really shallow, but I loved the way the women looked,” she said. “They had long hair and wore a lot of eye makeup and they didn’t look like the women in the nylons and high heels.”

The reality of her accomplishment was hardly less astonishing.

But first, she endured some hard times.

She also started getting more and more into the underground comics scene, and moved back out West, to San Francisco with her boyfriend, cartoonist Kim Deitch, in 1969.

Robbins was excited about underground comics, but she found it hard to get attention, let alone support from many male cartoonists.

“They didn’t want any girls in their boys club,” she said. “The wives and girlfriends would even do things like color in the art, and they would sell their stuff for them at conventions. There was nobody selling my stuff for me and I resented the hell out of it.”

She also found the misogyny in the underground comic scene increasingly disturbing. Some men, like R. Crumb, drew comics about rape and murder and thought her failure to find them funny meant she had no sense of humor.

In 1969 she read an article in the Berkeley Barb about how women weren’t really allowed to speak or make decisions.

“They were always so supportive, they loved me and were good to me and I loved them.”

Asked about that, she excitedly says she still remembers what they sang and breaks into “Dream A Little Dream of Me.”

Stars shining bright above youOn the day we spoke, Robbins sat in a café across the street from her house in San Francisco, having a bagel and coffee. She had just gotten back from a Comic Convention in Argentina, where, she said, she had a wonderful time.

Night breezes seem to whisper ‘I love you’

Birds singing in the sycamore trees

Dream a little dream of me.

Wearing a blue sweater and blue nail polish, Robbins seemed outgoing and chatty.

In the book she describes being so shy as a child that she would wait until the bell was about to ring before going in the schoolyard, so she wouldn’t have to spend any time outside with the other children with no one to talk to.

So what changed? What gave her the gumption that allowed her to start going into the offices of MAD magazine unannounced, to wear miniskirts, and to hang out with famous people?

“I have no idea,” she said.

“I have no idea,” she said.

She also dreamed of living in Paris, wearing a beret, and making art. Her goal was to be a bohemian.

The reality of her accomplishment was hardly less astonishing.

She published her first comics in the East Village Other in 1966. Then she went on to be published by Marvel, DC, and Kitchen Sink Press.

She produced the first all-women’s comic book in 1970, It Ain’t Me, Babe, and co-founded the anthology series Wommin’s Comix, which ran for 20 years.

And in the ’80s, she was the first woman to draw Wonder Woman.

In a period that she says is too painful to write about, she had her confidence destroyed by bad boyfriends and ended up in Los Angeles in the early ’60s, where someone told her she should pose nude for men’s magazines and become a movie star.

Robbins did this until she was “saved” by her first and only husband, a printer who bought her a sewing machine.

She designed and made clothes for herself and then started selling them at crafts fairs. She got a reputation for her work.

Sonny Bono approached her about making some outfits for him and Cher, but she turned him down because she avoided zippers and tailored clothes.

She did make clothes for Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas and for David Crosby and Donovan—although they couldn’t perform in the shirts she made for them, Robbins says, because the sleeves were dripping with lace that caught in their guitars.

After a dream about her father who she wanted to see before he died, Robbins left her husband and the folk music scene of the Sunset Strip and headed back to New York, where she opened a shop selling clothes on the Lower East Side, which she called Broccoli.

After a dream about her father who she wanted to see before he died, Robbins left her husband and the folk music scene of the Sunset Strip and headed back to New York, where she opened a shop selling clothes on the Lower East Side, which she called Broccoli.

Robbins was excited about underground comics, but she found it hard to get attention, let alone support from many male cartoonists.

“They didn’t want any girls in their boys club,” she said. “The wives and girlfriends would even do things like color in the art, and they would sell their stuff for them at conventions. There was nobody selling my stuff for me and I resented the hell out of it.”

She also found the misogyny in the underground comic scene increasingly disturbing. Some men, like R. Crumb, drew comics about rape and murder and thought her failure to find them funny meant she had no sense of humor.

Robbins said it resonated with her and she became a feminist. She began volunteering for a feminist underground newspaper, It Ain’t Me, Babe, and went on to edit and produce an entire feminist comic book of the same name.

Lately Robbins has turned more and more to writing, which she loves, and co-authored Women and the Comics, a series on historical female cartoonists, and Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896-2013.

Lately Robbins has turned more and more to writing, which she loves, and co-authored Women and the Comics, a series on historical female cartoonists, and Pretty in Ink: North American Women Cartoonists 1896-2013.

She recently worked on a project that meant a lot to her—publishing the 1938 book A Minyen Yidn, or A Bunch of Jews (and other stuff), that her father wrote in Yiddish about growing up in Belarus and Brooklyn.

Robbins has been taking Yiddish classes in San Francisco, and she found someone to translate her father’s book.

Reading it, she immediately decided his short, punchy stories would make a great graphic novel, and found a different artist for each story. She is delighted with the result, thinking her father would love it as well.

“I love seeing how artists interpret the stories,” she said. “My father is a writer and look what I do for a living.”

Last Girl Standing

Trina Robbins

Fantagraphics BooksPaperback

$19.99

ISBN: 978-1-68396-014-0

“I love seeing how artists interpret the stories,” she said. “My father is a writer and look what I do for a living.”

Last Girl Standing

Trina Robbins

Fantagraphics BooksPaperback

$19.99

ISBN: 978-1-68396-014-0

No comments:

Post a Comment