In his first cover for The New Yorker, which happened to be Tina Brown’s inaugural issue, Sorel pictures a barechested, pink “Mohawked rocker arrogantly draping himself on the seat of a horse” drawn carriage.

Sorel even gets the rocker’s shoes right. They are pointed like daggers at the back of the hapless driver. Traveling through the gorgeous autumn scenery of Central Park, our passenger might as well be Yeats’s rough beast “slouching towards Bethlehem.”

Taking their weekly unemployment checks of $35, Sorel and Chwast rented a cold-water flat on East 17th Street. Two weeks later they informed the phone company that in addition to the coin-operated phone on the wall, they wanted their very own private phone. “We were in business!” Sorel exclaims.

In ways, Sorel himself is a stranger in this world, a castaway from an earlier period. I’ll never forget an outfit he wore in the dress-down ’70s: a custom-made belted Norfolk jacket cut from heavy Irish wool. He was Beau Brummel in a world where it all hung out.

Edward Sorel has been compared to Daumier, Hogarth, and, in our own time, David Levine.

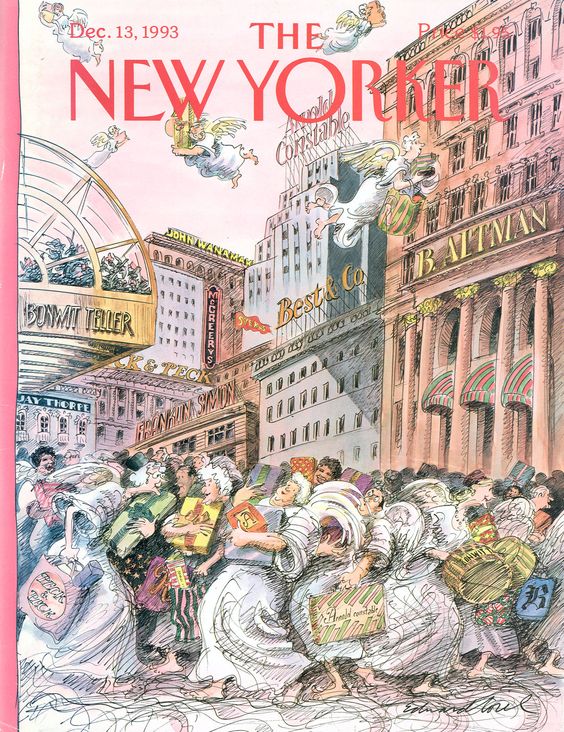

In another New Yorker cover, one of my favorites, Sorel lovingly portrays some of the many Fifth Avenue department stores that have bit the dust of wrecking balls: Jay Thorpe, Bonwit Teller, Arnold Constable, and Sloane’s.

Missing is De Pinna, one reader complained, and speaking for myself, I miss that hyper”elegant Black, Starr, and Gorham, shamelessly covered some forty years ago by a blanched ’60s facade.

At last count, Sorel’s covers have graced 41 issues of The New Yorker, and they form a chronicle of our time.

At last count, Sorel’s covers have graced 41 issues of The New Yorker, and they form a chronicle of our time.

A Mother’s Day cover portrays four decades of mother and daughter in the kitchen. In a 1934 tableau, Mom and her ringleted daughter bake a cake. Sixty years later, Mom is more harried; a cordless phone squeezed on her hunched shoulder, she orders from a Lotus Wok menu. Sprawling on the kitchen floor, her daughter lies transfixed before a TV.

In a Fourth of July cover, an overweight Uncle Sam struggles to squeeze into his striped pants. The metaphor is apt. We no longer fit a trimmer, more robust age.

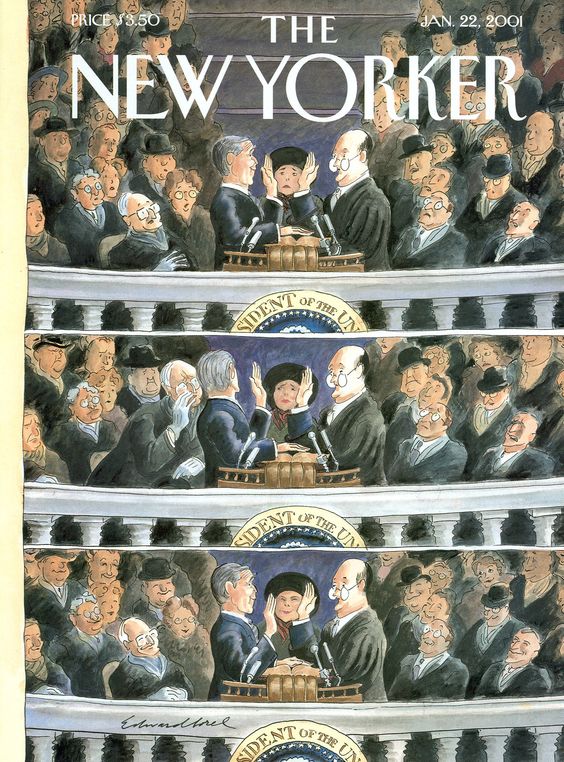

Recently, Sorel pictured George W. Bush at his inaugural. In the middle of the three”panel sequence, the President elect leans over to the Vice President for advice. Once given, he raises his right hand to take the oath of office. We are in for some ride, Sorel implies.

His covers, done for The New Yorker, The Nation, The Atlantic Monthly and TIME, bring to mind another chronicler of our time, the screenwriter Terry Southern, who captured the ’50s with Doctor Strangelove, and the ’60s with Easy Rider.

In the process, he released our deepest anxieties and gave voice to our fears about nuclear Armageddon and civil violence. “Poetry makes nothing happen,” Auden once wrote. Maybe so, but there is some virtue in a purgative.

And didn’t Uncle Tom’s Cabin, ringing like a bell in a darkening era, change the mood of half a nation?

Sorel’s road to success began on a rocky path. Born in the Bronx in 1929 to a father who was a door”to”door salesman of dry goods, he remembers his father as lounging whole days on the living room sofa. “I hated my father,” Sorel remarked.

His mother was the steady wage earner, working full”time in a millinery factory. Drawn to art as a teenager, he was accepted into the prestigious High School of Music and Art, but he remembers it as . . . “awful. They were full of theory, and drawing was discouraged.” It was only at Cooper Union that he began to draw alongside Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast.

“They were in the clique with the talented artists,” Sorel reminisced. “I was in the clique with the losers.” After Cooper Union, Sorel and Chwast worked briefly at Esquire magazine. They had the distinction of being fired on the same day.

“They were in the clique with the talented artists,” Sorel reminisced. “I was in the clique with the losers.” After Cooper Union, Sorel and Chwast worked briefly at Esquire magazine. They had the distinction of being fired on the same day.

But this proved salutary as they decided to join forces and form an art studio. It was called Push Pin after an occasional mailing piece, The Push Pin Almanack,which they self-published during their days at Esquire.

Several months later, Milton Glaser returned from a Fulbright year in Italy, and joined the studio.

Sorel quit Push Pin after two years. He felt guilty that “I was doing these cut-out pieces and not pulling my weight in the studio. Yet there I was, drawing the same $65 a week as Milton and Seymour.”

He left on the same day that the studio moved into plush quarters on East 57th Street. A poverty wish? Some friends have wondered.

Thrown back on himself, Sorel began to perfect his style of “direct drawing,” that is, inking directly onto the paper without a preliminary drawing underneath or a tracing below. “Working direct,” Sorel remarks today, “is fine art. Tracing is commercial art.”

What began as Stuart Davis' inspired cubism with The Push Pin Almanack and went on, according to Sorel, as Chwast and Glaser imitations, gradually developed into the distinct loose”line style for which Sorel is celebrated today.

What began as Stuart Davis' inspired cubism with The Push Pin Almanack and went on, according to Sorel, as Chwast and Glaser imitations, gradually developed into the distinct loose”line style for which Sorel is celebrated today.

In the early 1960s he moved to upstate New York. His close neighbor was the watercolor artist Robert Andrew Parker, who became a key influence on him.

Entering Sorel’s Soho loft today is like entering a private gallery. Stretching along either side of the long entranceway are his drawings and watercolors. Nearby are original works by some of his favorite artists: James McMullan, Robert Andrew Parker, Lee Lorenz, Arthur Szyck, Rowlandson, and the early New Yorker artist, Gluyas Williams.

Entering Sorel’s Soho loft today is like entering a private gallery. Stretching along either side of the long entranceway are his drawings and watercolors. Nearby are original works by some of his favorite artists: James McMullan, Robert Andrew Parker, Lee Lorenz, Arthur Szyck, Rowlandson, and the early New Yorker artist, Gluyas Williams.

Hanging alongside is a photograph of George Price taken by Sorel’s son, Leo, and letters to Ed from the ’40s Hollywood star, Mary Astor — Sorel is an avid cinephile — and Eleanor Roosevelt. In an adjoining room is his small studio.

Sorel works directly on lightweight acid-free bond paper — an Italian brand which is no longer produced, he laments. Each drawing consists of what he calls “finding lines” before he applies the definitive lines which give form and shape to his work. Once the ink lines are finished, the watercolor is applied.

“That’s the fun part,” he comments. “Coloring is always fun.” On some paintings he uses a wash made from a black china marker dissolved by rubber cement thinner. “You just use everything you can.” The paintings are then dry mounted on illustration board.

Sorel works directly on lightweight acid-free bond paper — an Italian brand which is no longer produced, he laments. Each drawing consists of what he calls “finding lines” before he applies the definitive lines which give form and shape to his work. Once the ink lines are finished, the watercolor is applied.

“That’s the fun part,” he comments. “Coloring is always fun.” On some paintings he uses a wash made from a black china marker dissolved by rubber cement thinner. “You just use everything you can.” The paintings are then dry mounted on illustration board.

In much of his work, Sorel deals with paradise lost. This leitmotif was explicitly stated in an autumn New Yorker cover in which Adam, expelled from Eden, walks knee-deep in a world strewn with leaves. God points to a rake.

Edward Sorel has been compared to Daumier, Hogarth, and, in our own time, David Levine.

But another comparison may be to Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener. When asked to act against his conscience, Bartleby’s refrain was, “I would rather not.”

Edward Sorel would also “rather not” do many things. He would rather not bow to authority. He would rather not mindlessly honor the sanctity of any flag or religion, creed or institution. He would rather not follow the latest fashion or play anybody’s game.

What he would rather do is speak his mind, fully, freely, and artfully. And we are all in his debt.

No comments:

Post a Comment