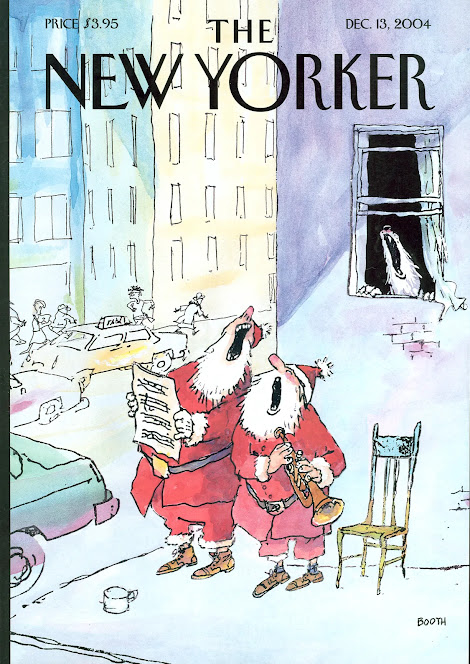

His cartoons usually featured older couples beset by modern complexity and interacting with cats and dogs.

Born on June 28, 1926 in Cainsville, Missouri, Booth was the son of schoolteachers; his mother, Irma, was also a musician and fine artist and cartoonist, and his father, William, became a school administrator in Fairfax, Missouri, where Booth grew up on a farm.

Born on June 28, 1926 in Cainsville, Missouri, Booth was the son of schoolteachers; his mother, Irma, was also a musician and fine artist and cartoonist, and his father, William, became a school administrator in Fairfax, Missouri, where Booth grew up on a farm.

Booth attended but did not graduate from the Corcoran College of Art and Design, the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, the School of Visual Arts, and Adelphi College.

Drafted into the United States Marine Corps in 1944, Booth was invited to re-enlist and join the Corps' Leatherneck magazine as a staff cartoonist; when re-drafted for the Korean War, he was ordered back to Leatherneck.

As a civilian, Booth moved to New York City where he struggled as an artist, married, then worked as an art director in the magazine world. He also worked on the comic strip Spot in 1956.

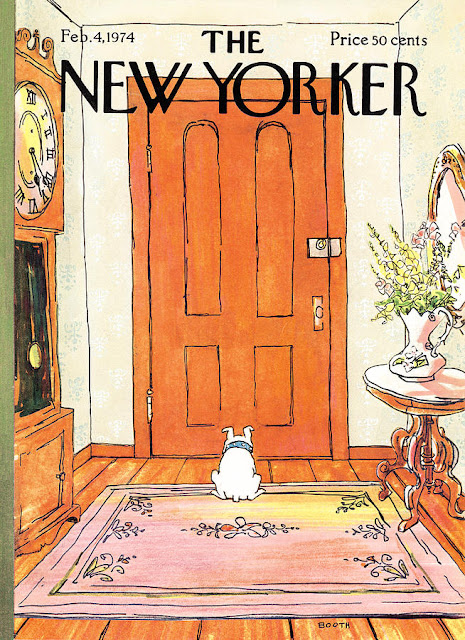

Fed up, Booth quit and pursued cartooning full-time, beginning successful in 1969, with the sale of his first New Yorker cartoon and has contributed to the magazine ever since.

Drafted into the United States Marine Corps in 1944, Booth was invited to re-enlist and join the Corps' Leatherneck magazine as a staff cartoonist; when re-drafted for the Korean War, he was ordered back to Leatherneck.

As a civilian, Booth moved to New York City where he struggled as an artist, married, then worked as an art director in the magazine world. He also worked on the comic strip Spot in 1956.

Fed up, Booth quit and pursued cartooning full-time, beginning successful in 1969, with the sale of his first New Yorker cartoon and has contributed to the magazine ever since.

|

| George Booth’s first New Yorker cartoon, in the issue of June 14, 1969 |

One signature element of Booth's generally messy or run-down interiors is a ceiling light bulb on a cord pulled by another cord attached to an electrical appliance such as a toaster.

Most of the household features in his cartoons were drawn from his own home. He described one of his cats, adopted later in his career, as being "more like my drawing than the drawings... when he lies down, his back feet go out in back — straight out."

He has illustrated many children’s books, including “Wacky Wednesday,” written by Dr. Seuss (as Theo LeSieg).

Booth also created the comic strip Local Item in 1986 and has also put out several collections of his work.

In the early two-thousands, he received the Milton Caniff Award from the National Cartoonists Society and an honorary doctorate of fine arts from Stony Brook University.

ALSO:

- "George Booth: 1926-2022", on Michael Maslin's blog.

- “George Booth 1926-2022”, by cartoonist Mike Lynch

- “Artist Spotlight: George Booth (1926-2022)”, by cartoonist Jason Chatfield

- “George Booth — RIP”, by D.D. Degg in The Daily Cartoonist

“Drawing Life with George Booth”, a documentary by Nathan Fitch.

UPDATE

Emma Allen from The New Yorker

George Booth Took in life and laughed

It was a line he’d first heard from his former boss at the consortium of trade publications—Rubber World, Modern Tire Dealer, Fast Food—where Booth served as art director before setting up camp in the pages of The New Yorker, in 1969.

Editors would come skulking into the boss’s office, begging for deadline extensions, only to be bawled out. Booth, meanwhile, was in there because he liked to take naps on the boss’s couch, and to enjoy the show.

Booth, who died this week, at ninety-six (one year younger than this magazine), was a man who took in life, drew it up, and then laughed and laughed.

Booth, who died this week, at ninety-six (one year younger than this magazine), was a man who took in life, drew it up, and then laughed and laughed.

A brief biography: He was born in the boonies of Missouri, a Depression-era kid with teachers for parents, who passed on to him their cheeky sense of humor.

Ma called Pa Billy, Pa called her Bill, the boys called her Maw Maw; we know her best as her cartoon avatar, Mrs. Ritterhouse, who contractually could appear only in the pages of The New Yorker (rights the magazine did not negotiate for, say, the Addams Family).

After high school, Booth was drafted into the Marines, and apparently hoped that service would lead to a career in cartooning. As many of his fellow-troops headed home from Pearl Harbor, he reënlisted; he’d been offered a position drawing for Leatherneck, the Marine Corps magazine.

He married Dione Babcock—who died just a few days before Booth—after seeing her in an all-women stage production of “Twelve Angry Men.” (You’ll never guess what they retitled it.)

He married Dione Babcock—who died just a few days before Booth—after seeing her in an all-women stage production of “Twelve Angry Men.” (You’ll never guess what they retitled it.)

The couple lived in Stony Brook, on Long Island, until they resettled in Brooklyn, in the apartment of their daughter, Sarah.

There, Sarah magnanimously coexisted with Booth’s “studio”—towers of sketches and doodles and marked-up newspapers which slowly encroached on her living room.

He entered my office on his first day of submitting cartoons to his new, deeply intimidated boss and brandished his cane, looming (inevitable, at six feet three) over my desk.

I quaked. “You are a ray of sunshine!” he hollered, and then let out that characteristic guffaw! I’ve always imagined that the lines of Booth’s drawings ended up so wobbly because of the uncontainable self-amusement of their maker.

Booth had come in from the anteroom where cartoonists waited, and in which he would meticulously rework his submissions—move a dog here, add a car tire there—by Scotch Taping bits of cut-up drawings over the cartoons he’d presumably been happy with when he left the house.

But, despite this frenzy of adhesion, he always had time for a cartoonist seeking encouragement or advice. He was a Pied Piper to many—not only to aspiring artists but also to neighbourhood kids, who’d trail him at block parties, begging him to draw something with sidewalk chalk.

He was boundlessly generous to those in his wake; after one visit I made to him and Sarah, he chivalrously insisted on walking me to the door, then had to be Socratically persuaded not to walk me to the subway, as he was in his pajamas.

For New Yorker readers, the name George Booth immediately conjures a world of insanely named (Reverend Dr. Clapsattle? Judy Klemesrud? Youbetcha?) porch-sitters, mechanics, cave-dwellers, bath-takers, military men, yokels, and churchgoers.

For New Yorker readers, the name George Booth immediately conjures a world of insanely named (Reverend Dr. Clapsattle? Judy Klemesrud? Youbetcha?) porch-sitters, mechanics, cave-dwellers, bath-takers, military men, yokels, and churchgoers.

The Booth universe is a detritus- and cat- and bull-terrier-packed place that his admirers have gleefully revisited over the years. The reams of fan letters he received during his long tenure included at least one proposal of marriage.

In the days after 9/11, when a return to normal life felt unimaginably hard, Booth supplied the sole “cartoon” in the issue following the attacks: a drawing of Mrs. Ritterhouse, her fiddle on the floor, her eyes closed in prayer, a cat nearby covering its face with its paws.

In the days after 9/11, when a return to normal life felt unimaginably hard, Booth supplied the sole “cartoon” in the issue following the attacks: a drawing of Mrs. Ritterhouse, her fiddle on the floor, her eyes closed in prayer, a cat nearby covering its face with its paws.

Booth was only nine when he joined the real Maw Maw for his first “chalk talk” on the stage of a Methodist church in Missouri, scribbling amusing pictures while she monologued to a crowd of pious biddies.

Her advice: “You stand there and act like you know something, whether you do or not!”

The day I met Booth, I copied that maxim onto a Post-it and stuck it to my office wall, where it remains, suddenly inert without the accompanying guffaw! ♦

No comments:

Post a Comment