From Boston.com

First off, he’s a New Yorker cartoonist, where he’s spent 25 years making light of, well, anything and everything, including current events for the Daily Cartoon on the magazine’s website. That’s where he did a cartoon about Boston that became the New Yorker’s most shared cartoon ever up to that point.

He’s also an editorial cartoonist, often for The Boston Globe, skewering the powerful and pointing out the absurdity that seems to run more and more rampant in the halls of power these days. It’s a dichotomy Weyant says he relishes.

Weyant — who’s also the illustrator of an award-winning series of children’s books written by his wife, Tufts alum Anna Kang — sat down recently to talk about his craft, that famous Boston cartoon, and how he managed to become a Nieman Fellow at Harvard, only the second cartoonist to ever hold that distinction.

Boston.com: So for people who may not know, tell us what being a fellow entails. It sounds very important.

Christopher Weyant: It’s basically Eustace Tilley from the New Yorker, I dress like that — top hat, ascot … and you know it’s at Harvard, I don’t know if you heard that. So that means you have to find ways to work that into every conversation: ‘How’s the weather?’ ‘Well, it reminds me of a story when I was at Harvard and they had weather.’ [laughs]

So being a [Nieman] Fellow, it’s a really phenomenal journalism fellowship, and I honestly feel very blessed to be a part of it, and I don’t know what they were thinking by having me.

But it’s these great 24 fellows, 12 from the United States, the other 12 from overseas. And they’re journalists and producers and TV and war correspondents and war photographers, and even a cartoonist.

And so the program is basically a time out for you to take courses at Harvard — actually, it’s free tuition at MIT, Harvard, any of the Boston area universities.

And so the program is basically a time out for you to take courses at Harvard — actually, it’s free tuition at MIT, Harvard, any of the Boston area universities.

And you talk about a study plan that you want to research, and some people turn those into books or studies; I had one about cartoons.

And then you have a whole year to kind of take a break and reinvest in yourself, which is just insane — it’s a paid fellowship, so you can actually do it. And it was amazing. And then you get to say you’re a fellow.

How far along were you in your career when that came about?

It was 2015. I had been working at the New Yorker for some time, and I was also a cartoonist at The Hill in Washington, D.C.

So then I got the chance to apply, and it was kind of a real Hail Mary of a thing, but it really was not only wonderful but life-changing.

How far along were you in your career when that came about?

It was 2015. I had been working at the New Yorker for some time, and I was also a cartoonist at The Hill in Washington, D.C.

I was with them for I think 15 years, or something like that. And then I had an opportunity where I had a little bit of space, which we also call a layoff …

They took out a couple of staff members, and I was one of them.

So then I got the chance to apply, and it was kind of a real Hail Mary of a thing, but it really was not only wonderful but life-changing.

I came away with great friends. And although it sounds really kind of pompous, it’s not.

It’s really lovely people, very supportive journalists, and it was like having your own newsroom, really positive. And then that was a period to pivot.

What was your original cartooning work like? Where did you get your first break?

I was working at this think tank in New York, the Council on Foreign Relations, working for the magazine Foreign Affairs.

I was really happy there, I was working in advertising for them. I always cartooned my whole life, but when I was younger and growing up in New Jersey, becoming a cartoonist was not a real job.

It wasn’t like now with graphic novels and animation. So even though I cartooned my whole life I never even thought it could be a career.

Then my brother was working on a Westchester County newspaper and an opportunity opened for me to do local cartoons.

Then my brother was working on a Westchester County newspaper and an opportunity opened for me to do local cartoons.

They were doing an open submit — I submitted, they picked mine, and I can’t remember, it was like for 5 bucks a cartoon, or maybe nothing a cartoon, and it was once a week on local northern Westchester County topics.

And I loved it so much more than my regular job.

I had that 27-year-old kind of come to Jesus moment when you’re like, ‘Well, something’s wrong here.’

And so I ended up saving money for a whole year and said, ‘OK, listen. I’ll quit, and if my COBRA insurance is at 18 months and I run out of health insurance and it’s not working, I gotta go back.’

But I didn’t. I never went back.

When did the New Yorker come into the picture?

I had been doing a couple of years worth of cartoons, strips and gag cartoons, but doing it for smaller magazines.

I had my skills that I learned at Foreign Affairs of contacting people, I knew how publishing worked, [how to] work my way in and make calls and pitch them, and so I went into the New Yorker and I said, ‘Can I drop off my portfolio?’

And I did, under Lee Lorenz, who was the old cartoon editor — phenomenal cartoonist, and a great editor, too.

You couldn’t meet him, you just gave them your portfolio, and then you came back a week later, and it was slid through the window.

I’ve had high-end deposits which were less [secure]. [laughs]

He gave me back a note, which was, you know, ‘Great stuff, not this time, but like to see more’ — I still have that note.

And then it took me a whole year to come up with a batch, literally a whole year.

In that time Bob Mankoff had come in [as cartoon editor], and then I think a month after I submitted I got in with my first cartoon.

You do two very different types of cartooning: the editorial cartoons that people see in The Boston Globe, and the gag cartoons that run the New Yorker. What is the difference in the creative process when you sit down to create either one or the other?

They’re both cartooning, but they’re really different art forms — it’s a different pacing, and I think it produces a different effect.

They’re both cartooning, but they’re really different art forms — it’s a different pacing, and I think it produces a different effect.

With the New Yorker stuff, it’s about everything, social stuff, relationships, and sometimes just silly, funny stuff, right? Which is great.

And then sometimes there’s stuff that’s hyper-topical, and we would do that for the Daily. The Daily Cartoon on the [New Yorker] website started with David Sipress, and then Danny Shanahan was the second. I was the third.

And so when you’re writing them there [for the Daily], it’s just a different sort of process.

And so when you’re writing them there [for the Daily], it’s just a different sort of process.

The kind of cartoons I write, whether it’s for the Globe, or whether it’s for the New Yorker, they have this in common, that I’m trying to write a cartoon that’s an evergreen that’s also hyper topical.

That’s what I’m shooting for, whether I get there or not.

Sometimes it doesn’t work, and sometimes it does.

But the idea is like with a New Yorker cartoon, I can do a cartoon that kind of stands alone as its own gag, but when it’s put into the context of the day it’s about, [say], gun control, right?

That’s a really fun challenge to present yourself with, and you get something that hits twice.

With the Globe, it sometimes gets a little broader in its scope, because with the New Yorker cartoon there is a difference from regular editorial cartooning in that it’s so in-the-silo — we’re talking to a very highly educated and highly progressive audience and more or less everybody’s on board.

And so the humor tends to be a little funnier, because you can make bigger jumps, because we know you know all the information.

I don’t have to have the newspaper sitting on the side that says what I’m talking about, just to keep the audience on board.

The other part is that it tends not to have the same kind of bite, right?

The other part is that it tends not to have the same kind of bite, right?

That’s the downside … You sacrifice some of the laugh, I think.

Yeah, there’s nothing there. [laughs]

I think the problem everybody faced was like, how do you make a buffoon look more like a buffon?

And just before the deadline he would always have something else that was just outrageous, you know, just because he’s good at manipulating the media and our attention by constantly getting us to go after that shiny thing.

So the cartoons tended to be a little bit angrier and a little more defiant.

So the cartoons tended to be a little bit angrier and a little more defiant.

And as we got into his administration, it felt more and more crazy — like we were on the other side, and people were really starting to lose respect and hope about our government, let alone whoever the president is.

That’s when the timbre changed for what I think a lot of us were doing.

And then the responses that we got were completely different than I have ever gotten before.

We had a lot more people who were appreciative for making them not feel crazy.

That was actually the biggest through-line, how many people would actually thank me — and it wasn’t just me, I heard this from a lot of cartoonists — thank me for giving me a laugh, or making me know which way is up, or speaking out because it felt like [things were] just kind of falling apart everywhere.

And just having a little bit of rebellion in the air [from] a stupid cartoon still feels a little freeing or something, I don’t know. But we all were getting that kind of feedback, which was nice.

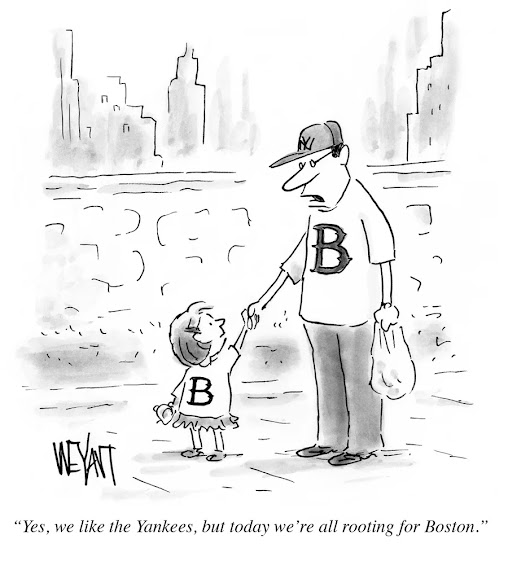

Right after the Boston Marathon bombing, you did a New Yorker cartoon that showed a father and daughter wearing Boston jerseys and the father says, ‘Yes, we like the Yankees, but today we’re all rooting for Boston.’ It’s so hard to capture the feeling after an event like that, but that cartoon did a really good job of it.

I learned a lot from that cartoon, and thank you, I’m glad you liked it.

I was the Daily cartoonist for the first run. So that was my first round on it, and having been a political cartoonist, I know what it’s like …

I was on deadline for 9/11, literally the first cartoon about 9/11 was mine.

It was a piece of sh—, but it was mine.

I was working for The Hill, and I had something penned, I think, before the second tower was down.

It was one of these garbage cartoons, but it’s the worst thing that can happen to you. Because what do you say? You don’t want to be funny, and I can’t stand these maudlin [cartoons] …

But we did that cartoon for the Boston bombing, and that’s why we [still] have the Daily Cartoon.

It was the most widely shared cartoon in New Yorker history at the time.

Diane Sawyer closed her newscast with it.

And I had no idea, because I was in the basement working away, getting on to the next cartoon because I had another cartoon the next day, and then the thing went crazy.

But that one really did touch [people], and my whole family has a real connection to Boston, and I’m a Boston Red Sox fan in Yankee country, so it really …

But that one really did touch [people], and my whole family has a real connection to Boston, and I’m a Boston Red Sox fan in Yankee country, so it really …

Wait, what? You’re from Jersey and you’re not a Yankees fan?

I just can’t be a part of any team that happy.

I just can’t be a part of any team that happy.

My father’s mother, my grandparents, are from Kennebunkport, and [they] were old school — we were pre-pennant Sox fans.

We’re the long-suffering … my dad lost a fortune betting the neighbors and losing every single time.

That explains why the Globe lets you do cartoons for them — at least you’re a Red Sox fan.

Exactly. I love the Sox … I took my dad up there [to Fenway Park] on his 75th birthday and called ahead and tried to pretend I was somebody famous, and they got us up in the back and gave us a tour around, and it made his day.

When we talked to New Yorker cartoonist David Sipress, he told us about when he got a call from the Sox ownership to compliment him on a Red Sox-related cartoon and offer him a spot in the owner’s box for a game. He made the mistake of mentioning on that call that he was a Yankees fan, and he never heard from them again.

Sometimes you’ve gotta keep your mouth shut, and that’s the problem with the Yankee fans, right? They never keep their mouth shut.

No comments:

Post a Comment