|

| Illustration by Dylan Teage |

An essential collection for serious comics fans

Michel Faber

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 8 December 2011 12.50 GMT

|

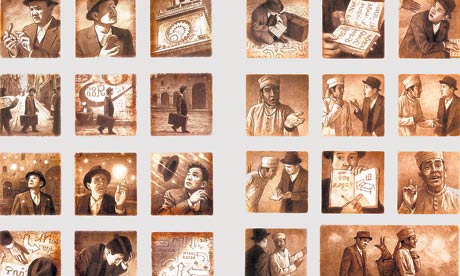

| Culture shock: The Arrival, Shaun Tan's sepia evocation of immigrant experience. |

Terry Gilliam, accorded equal billing with Gravett, seems to have been roped in mainly for his celebrity value, as his two-page foreword amounts to nothing more than a few amiable anecdotes. One of these, about the illicit stash of Adventures of Flesh Garden that alerted his parents to "the sex-mad beast that was being spawned in their son's rapidly changing body", bolsters the clichéd view of comics as the fantasy fuel of adolescent boys and undermines what the next 953 pages seek to prove: that comics address a marvellously broad range of experience and can appeal to anyone. The choice of cover illustration – Judge Dredd toting a massive gun – typecasts the demographic still further.

A pity, because this book is more inclusive, more useful and less culturally blinkered than other 1001 Before You Die efforts. It belongs in the home of anyone who is serious about investigating this boundlessly fertile art form. And there are many readers who have yet to begin that investigation, despite comics' long history. (One of the earliest items in this chronological exploration was produced by Gustave Doré in 1854.)

The word "comics" in the title has a necessarily elastic scope. Sometimes it means standalone graphic novels, sometimes individual issues of a comic series, sometimes notable storylines within a series, and sometimes entire runs, such as the 102 issues of Fantastic Four produced by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. All titles are given in English, although not all are available as such (Tomaž Lavric's Bosanske Basni is listed as Bosnian Fables, but the nearest Lavric's book has got to our island is the French edition). Indeed, the imperviousness of British and American tastes to some continental institutions is remarkable: Gaston, the Belgian slacker whose exploits have charmed Europe for half a century, was once trialled for a few pages in a 1990s American anthology as "Gomer Goof" and then abandoned. In the world of comics, as in literature generally, there is no assumption that what interests a million Europeans should automatically be offered in English.

Manga and bandes dessinées are heavily represented but there are welcome contributions from Sweden, Germany, Norway, China and a host of exotic elsewheres. I enjoyed the unintentional humour in Hemant Sareen's dispatch from New Delhi: "India's first graphic novel, Orijit Sen's The River of Stories, has remained a hallowed presence on the Indian comics scene despite being out of print since it was published." Gabriella Giandelli's eerie meditation on the life of a building, Interiorae, and Gipi's chronicle of moral erosion, Notes For a War Story, were unknown to me a week ago, but are now on my wish-list. A longtime favourite of mine, the Spanish satirist Miguelanxo Prado, gets his due, and what a delight to see Australia's Michael Leunig finally receiving some recognition in this country.

While each selection is deemed a classic of its kind, no attempt is made to filter out the kids' stuff from the erotica, the meditative memoir from the superhero slugfest, Palestine from Peanuts, Maus from Mickey Mouse. Sensible as this policy might be, it does mean that terms such as "powerful", "complex", "hilarious", "profound", etc, are even more relative than usual. It's doubtful whether a reader who admired the disturbing ambiguities of Phoebe Gloeckner's A Child's Life would find the simplistic melodrama of a 1970s Iron Man storyline "challenging and provocative", or whether a reader gobsmacked by The Arrival, Shaun Tan's sepia evocation of immigrant experience, would find Spider-Man: Clone Saga "astounding".

If this book is to function as a guide to essential purchases, each reader will need to ponder each entry with a dash of scepticism to avoid being disappointed. In this respect, Gravett's Graphic Novels: Stories To Change Your Life was superior, in that it reproduced many entire pages of the comics, allowing you to evaluate the artwork and script for yourself. Most of the illustrations here are reproductions of covers, accompanied by précis that can occasionally be opaque ("the mushi are described as something close to the core of life", observes a contributor from Japan).

Any encyclopaedic survey provokes criticism for what it omits, and 1001 Comics, despite its wrist-straining bulk, is no exception. Before you die, you're urged to read no fewer than five Tintin books but none by Dave Geiser, Roberta Gregory or Dick Matena. There are several pornographic artists covered (by female scholar-enthusiasts) but Ignacio Noé, the best practitioner still alive, is overlooked. It's regrettable, too, that Melinda Gebbie, whose 1980s undergrounds were more distinctive and better-drawn than many featured here, is noted only for her recent collaboration with her husband, Alan Moore. And so on. Each fan will have his or her gripes, but we should celebrate what's included: the overwhelming majority of the art form's greatest achievements, and plenty of its underappreciated gems.

Ah, but I know what you're thinking, those of you who'd like to get to grips with this medium but are dutifully consuming Julian Barnes' Booker-winning chef-d'oeuvre instead. How can you be seen reading a tome with Judge Dredd on the cover and Hellboy punching demons inside? Well, look at it this way: studying 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die is like visiting the world's most fabulously well-stocked comics shop. This virtual emporium may be far superior to Forbidden Planet, but it can't afford to ignore its regular customers. If superheroes, homicidal maniacs and feisty animals are not your thing, you'll just have to tolerate them as you discover a wealth of other delights. Eventually, the realisation may even sneak up on you that a good superhero comic is better than a bad literary novel. Jack Kirby's New Gods or Martin Amis's The Pregnant Widow? Pow! No contest.

• Michel Faber's The Fire Gospel is published by Canongate.

No comments:

Post a Comment