—John Lennon

|

| Photo: Eamonn McCabe/The Guardian |

I have featured earlier, on this blog, great cartoons by Ronald Searle.

You will find a complete list of tributes to the British cartoonist in the Perpetua website.

For those who don't know his work, here is a brief sample:

From the Desk of Bob Mankoff:

HAND VS. HEAD: THE CARTOON GENIUS OF RONALD SEARLE

I don’t really have much to add, in words, to the outpouring of tributes to the British cartoonist Ronald Searle, who died last week at ninety-one, except to concur completely. When it comes to a unique graphic style and comic vision such as Searle’s, my impulse is to show before I tell. So here are a few, too few, illustrative examples from the pages of The New Yorker:

|

| Rembrandt meets Thurber |

|

| Magritte meets William Tell |

|

| Ford meets Sherman |

|

| Giacometti meets Olive Oyl |

A more complete selection of Searle’s New Yorker work is available here. Of course, that more complete selection is still very incomplete because Searle’s cartoon legacy doesn’t rest primarily or even in a minor way with The New Yorker. Of his many thousands of published drawings, in hundreds of publications, here and in countries around the world, just seventy-nine appeared in our pages. So I was a bit surprised that the drawing chosen to be representative of his art in this week’s New York Times obituary was one of our covers.

But maybe it’s not so surprising, because the cover does, in fact, represent a defining essence of much of Searle’s work.

But maybe it’s not so surprising, because the cover does, in fact, represent a defining essence of much of Searle’s work.

My friend Sam Gross classifies cartoonists as either as “heads” or “hands.” A “head” cartoonist needs a strong idea to have a good cartoon. No idea, no cartoon. It’s not that the drawing doesn’t matter; it does, but it’s a bonus. For a “hand” cartoonist, a category in which I place Searle, it’s mostly the other way around. The drawing is the main show, the raison d’être—the drawing is made better by a good idea, of course, but it’s still well worth taking in regardless.

The individual elements in this cover, from the slyly contented cat to the splendidly rococo desserts, are all graphic comic charmers in and of themselves. It all works even before we “get” the idea, which, in this case, I don’t completely. For myself, as a “head” cartoonist, the idea on this cover is actually somewhat confusing. Thought balloons in cartoons like this usually represent desire. Fair enough, the cat wants a fish. But does he desire a fish instead of these lovingly drawn desserts? Hmm. Then why does the cat have that slight smile running across his face? If this were just a simply drawn “head” cartoon, by someone like me, it wouldn’t merit much attention, but because it came from the outrageously talented hand of Ronald Searle, we remain transfixed and as contented as that cat.

Bob Mankoff

Gerald Scarfe interviewed in The Guardian:

Ronald Searle: Now let's have some fizz

Ronald Searle was a cartoon genius – as generous with his advice as he was with pricey champagne. Gerald Scarfe remembers his friend and childhood hero.

I was an asthmatic child and didn't get much of an art education. But then, at the age of about 14, I discovered Ronald Searle. He was working as a cartoonist for the News Chronicle and Punch magazine, doing wonderful, satirical portraits of people such as the Archbishop of Canterbury. He became my hero. I found out where he lived and used to cycle over to Bayswater from Hampstead, composing what I would say to the great man. His house had a green door with a brass doorbell – but I could never get my fingers to ring it. I was too afraid. I would get back on my bike and cycle home, feeling dismal.

A few years later, my wife Jane Asher organised a secret meal for my birthday at this exclusive restaurant in Provence. When we walked in, the only other people there were Ronald and his wife. It turned out they had lived in this town for years. A beautiful little package sat on the table, all done up with ribbon. I said: "Oh, is this for me?" And Ronald said: "Yeah, it's nothing." So I opened it, and there was a brass doorbell with a note saying: "Please ring any time."

We became great friends, meeting up in that restaurant every year. Ronald had a wonderfully dry sense of humour. Once a year, he would pay the restaurant with a picture: pigs going into the kitchen looking doubtful, or snails crawling on to people's plates. We would always find pictures waiting for us at the table: Jane would have a drawing of a cat wearing a ballerina's outfit or putting lipstick on in front of a mirror; and I would have a bearded, scruffy cat, scratching his head, pens and paper laid out, waiting for his cartoon to come. Ronald made me laugh so much: although he was an elderly man, he didn't have an old mind at all.

I'll always remember his kindness: he was laudatory about my work, and would send me pages telling me what he liked about it. He used to love sitting and talking about art. After our meal in the restaurant, we would go back to his house for what he called "a little bit more engine oil" – meaning an expensive champagne that he loved. He and I would discuss all the art around. He was quite acerbic: if he didn't like something, he didn't pussyfoot. Even in his late 80s and early 90s, he was still worrying where the next job was coming from. He just wanted to keep working and drawing. Luckily he was able to – right to the end.

Ronald didn't just draw funny little men with big noses: he taught me that you have to take the caricature from the character. If you're drawing Margaret Thatcher, she must look cutting and acerbic, because she's that sort of woman; whereas if you were drawing John Major, you couldn't possibly make him that way. Ronald showed me that you have to really look at a person and assimilate what they are, then let that flow out on to the paper. He was one of those artists who could really draw properly. Many just think the idea's the thing – that you can get the idea and then just do a little scribble. He'd spent his early years in a Japanese prisoner of war camp: it's extraordinary to think that this thin, wiry little man survived that and came back to make us all laugh.

People think of Ronald's style as very British, but he didn't see himself that way. He was very popular in Europe: over the last decade, he drew political cartoons for Le Monde, and a museum in Hanover recently bought most of his work. I'm glad somebody did – but it's a bit of a disgrace that it wasn't a British gallery.

He didn't like talking about St Trinian's. He created the strip early in his career, back in the 1950s, and it became a huge monster he couldn't control – especially the new films. He did tell me that he was paid something pitiful for the first St Trinian's movies featuring Alastair Sim and all those old stars.

Although he was always popular, I'm not sure Ronald felt appreciated as an artist in this country. There's a strict delineation between cartoonist and fine artist over here that doesn't exist in Germany and France. Cartoonists are often regarded as people who just dash things off on envelopes for a quick joke. My sadness is that he was never knighted, although I don't suppose Ronald cared a stuff.

Interview by Laura Barnett.

Guardian cartoonist Martin Rowson on the genius of Ronald Searle's line:

Blots on a landscape

I’m not entirely sure if I should be furious or flattered, but on the BBC 10 O’Clock News on the day Ronald Searle’s death was announced (and later on the website) they showed an image, purportedly by the great man, which is in fact a Searle pastiche I drew for a BBC4 documentary on Searle I presented in 2005. This, perhaps, is just par for the course from an organisation which centred its reporting of Searle’s death around “St Trinian’s Cartoonist Dead”, in spite of the fact that, beneath the headline, Searle himself had been trying to forget all about St Trinian’s for nearly 60 years.

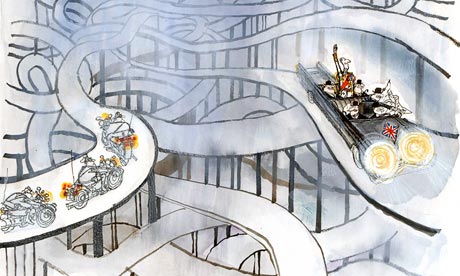

Still, this crass Beeb blunder provides an opportunity to explore an aspect of Searle the headline obituarists have chosen to ignore, and that’s his “line”. On both the BBC4 show and at a talk during the 2010 Cartoon Museum Exhibition to celebrate Searle’s 90th birthday, I had a chance to have a stab (and that’s the appropriate verb) at the way Searle drew. On the second occasion, I was even using some of Searle’s own pens and nibs, including one made out of bamboo (later he actually sent me a box of his own pens), and though it takes a lot of practice and nerves of steel, eventually if you try hard enough you can unveil surprising new truths simply through imitation.

For example, Searle’s scratchy style is hardly in evidence in the first St Trinian’s cartoons, even though these are, apparently, his most important work. It’s only later in the 1950s you can see him begin to use the nib like a cross between a chisel and a stiletto: he bends and twists the tines of the nib to widen and contract the line, stretching into a wisp of gossamer and flattening it into a splodge, but with the point of the pen never leaving the surface of the paper for a second.

This in itself is daring; but what he did next was close to genius: he started to overdraw. That means he started breaking the basic rule of graphic representation, whereby a horizon behind the perpendicular of a tree in the foreground is shown to be occluded by the tree: the line, in other words, breaks the horizon’s line, to maintain the illusion of recreated reality. But not with Searle. I don’t know whether it was deliberate or even conscious, or he just liked the look of it, but once he broke both the line and the rules, his work becomes something almost transcendentally beautiful. As someone once said to me about the way the great Ralph Steadman pulls off the same trick (thanks entirely to Searle), it marks the difference between the controlled, constrained artifice of pornography and the joyous explosion of freedom you find in true art.

Bothering to analyze those spatters of blots – which bedeck the paper like fireworks or champagne bubbles – may seem to be impossibly arcane. I doubt Searle thought too deeply about it himself. But it’s worth teasing out another thread in Searle’s work: how he recorded the torture and deaths of his fellow POWs working on the Burma Railway, and by furtively recreating reality thus brought it under some kind of redemptive control; how he then took those experiences – and sometimes the actual composition of his Burma drawings – and again recreated horror into (albeit dark) comedy in the St Trinian’s cartoon, achieving further redemption by laughing reality deeper back into its stinking lair. His way with a line then provided the propellant that sent him soaring off into true genius.

And all of that is at least part of the reason why the St Custard’s “skool dog thinking” (above) remains one of the most beautiful British illustrations of the mid-20th Century.

Martin Rowson' obit: Ronald Searle was our greatest cartoonist – and he sent me his pens

Ronald Searle interviewed by the BBC on the occasion of his 90th. birthday:

Martin Rowson' obit: Ronald Searle was our greatest cartoonist – and he sent me his pens

Ronald Searle interviewed by the BBC on the occasion of his 90th. birthday:

No comments:

Post a Comment