This memoir of a particular time and place is as much about why Groth never advanced at the magazine as it is about Groth’s fascinating relationships with poet John Berryman (who proposed marriage), essayist Joseph Mitchell (who took her to lunch every Friday), and playwright Muriel Spark (who invited her to Christmas dinner in Tuscany), as well as E.J. Kahn, Calvin Trillin, Renata Adler, Peter DeVries, Charles Addams, and many other New Yorker contributors and bohemian denizens of Greenwich Village in its heyday.

Here, Janet Groth answers questions about those people and that place…

What’s the funniest thing a writer said to you?

Algonquin BooksNot easy to choose when your workplace is surrounded, as mine was, with the world’s funniest cartoonists trying out gags on you, or humor writers like Peter DeVries and Calvin Trillin dropping bon mots as they pass your desk.

But, the Editor-in-Chief William Shawn was pretty funny, too. He once sent word through an envoy that my planned holiday party would have to be cancelled. Why? “We can’t possibly be discovered engaging in the very activity the magazine has been making fun of for years.”

Sounds like a New Yorker cartoon, doesn’t it? Take Charles Saxon’s, for example, in which a woman in Capri pants is talking on the telephone: “But you must come! We’re only having people who hate New Year’s Eve parties.”

What’s the oddest thing a writer ever did?

What’s the oddest thing a writer ever did?

Let me think. Was it Charles Addams rigging up an antique electric chair to decorate his corner office?

Was it Croswell Bowen, off his meds and making a lightening-fast nude appearance in the hall before quick-thinking colleagues threw overcoats over his pasty shoulders?

Was it St. Clair McKelway marking up the office walls with vulgarities while undergoing a manic phase?

Was it a couple of Talk reporters tearing down the wall between their offices, the better to party en suite?

In an establishment known, as one writer put it, “as the employer of the congenitally unemployable” the possibilities are endless.

Who was the writer you most wanted to be like and why?

Who was the writer you most wanted to be like and why?

Once I got rid of my cluttered syntax, a legacy of my fondness for Henry James, I wanted to write like Joan Didion, all spare style and sophisticated bleakness. I found her mix of Malibu and angst very appealing.

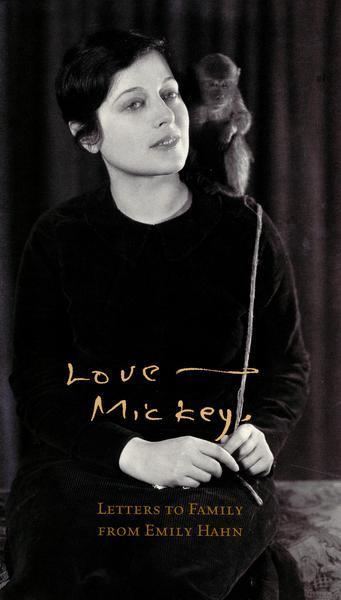

But the New Yorker writer I most wanted to be like was Emily Hahn. She was a famous beauty in her day and any feminist’s or any woman’s ideal.

Author of China to Me, one of the best memoirs to come out of World War II, “Mickey” Hahn, as all her friends called her, had known incarceration in a Japanese prison, made a patriotic stand for female prisoners of war, had a wildly romantic affair with a British war hero and, after bearing him a daughter, managed to combine an international career in journalism with conscientious motherhood.

It was not the war experiences or the problematic romance that I envied, (the dashing Brit was married), but her courage and elan in very trying circumstances.

Who is the writer now who you most want to be like and why?

Who is the writer now who you most want to be like and why?

Three recent writers of memoirs have blown me away.

Mary Karr’s The Liar’s Club, Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle, and Jeanette Winterson’s Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? all vividly evoke childhoods as victims of abuse and neglect but completely without self-pity.

Reading them and noting how tame my own material was beside theirs, I despaired of ever being able to write a book worthy to be in their company.

But, when I take a more nuanced look at the five decades of struggles toward selfhood my book depicts, and give myself some credit for having found my own voice at last, I am content to say that I, I am the writer I most want to be now.

The book you read that changed your life?

The book you read that changed your life?

Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, along with books by Germaine Greer and Kate Millett, exploded my world in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s — giving me a view of women as victims of male sexism in a patriarchal society.

When men responded to the news that I was preparing to teach college English with, “Why would you take a job away from a man who has to have it to support his family?”

I now could stick up for myself. I got into a long dinner table fight with the lawyer husband of a college friend who argued that his firm need never offer partnerships to women who would only take the firm’s perks and abandon them for childbirth at some crucial point in a major litigation.

Thanks to those gutsy women writers, the situation has evolved enormously in the decades since — or has it?

The book you read at The New Yorker?

The book you read at The New Yorker?

I was always reading, either the magazine itself or the books I needed to master in preparation for my Ph.D comprehensive exams. Let’s say my daily fare, when I wasn’t answering the phone, involved everything of merit in the English language from Beowulf to Virginia Woolf.

The writer you never wanted to deal with?

The writer you never wanted to deal with?

I was terrified of Edmund Wilson and kept my head down whenever he was using office space on my floor, lest I come under his censorious eye and get a tongue-lashing in his high-pitched stentorian voice.

There is irony here in that Mr. Wilson became a means to an end for me in my academic career. Having chosen the late writer for my dissertation subject, he was my constant subject of study for the twenty years to follow.

I came to know him intimately, a term I use deliberately to indicate that even his love life was under my scholarly scrutiny as co-editor of his personal correspondence and, in one final burst of Wilsoniana, as co-author of his romantic biography covering his wives, mistresses and romantic interests of every stripe. Truth to tell, I still wouldn’t have wanted to deal with him in person.

The writer who you thought was the most handsome?

The writer who you thought was the most handsome?

Oh, dozens! I have a wide – you could say a catholic — taste in men. John Brooks was the New Yorker’s business correspondent and was a silver haired vision of manly grace. The two of us had eyed each other appreciatively for a decade or more when, long after I left the magazine we found ourselves on the outs with our significant others long enough for a date.

We had a lovely evening together, which involved dinner at Le Perigord and “Treemonisha” at the New York City Opera. As it turned out, only an interlude in each of our lives, but one leaving behind the special glow of a whim gratified.

The Receptionist: An Education at The New Yorker

Janet Groth

Janet Groth

320 pages

No comments:

Post a Comment