William Grimes in The New York Times.

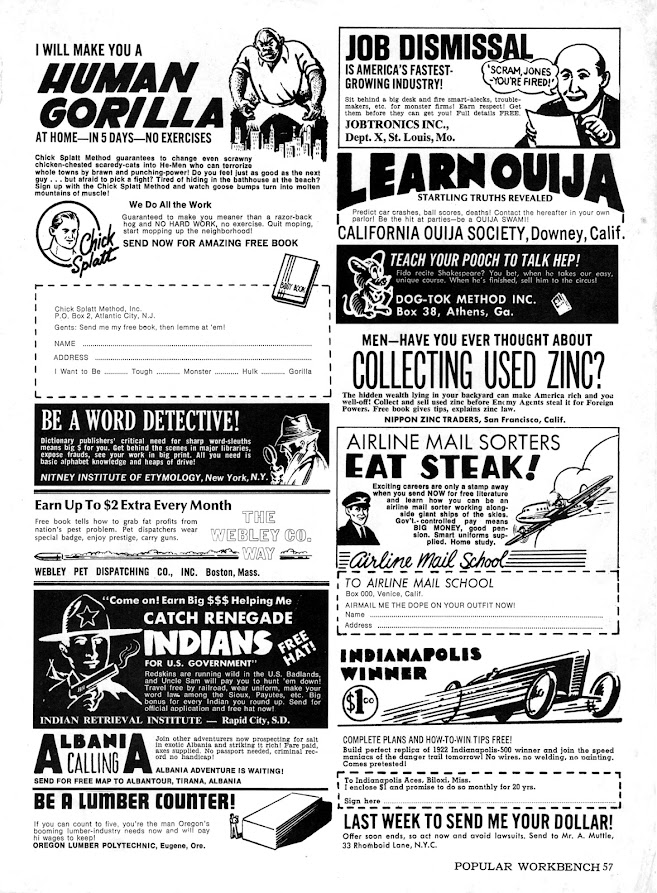

Borrowing from the advertising style seen in magazines like Life, Look and Collier’s in the 1930s and ’40s, Mr. McCall depicted a luminous fantasyland filled with airplanes, cars and luxury liners of his own creation.

It was a world populated by carefree millionaires who expected caviar to be served in the stations of the fictional Fifth Avenue Subway and carwashes to spray their limousines with champagne.

“My work is so personal and so strange that I have to invent my own lexicon for it,” Mr. McCall said in a TED Talk in 2008.

“My work is so personal and so strange that I have to invent my own lexicon for it,” Mr. McCall said in a TED Talk in 2008.

He called it “retrofuturism,” which he defined as “looking back to see how yesterday viewed tomorrow.”

A wider audience knew Mr. McCall through the collections “Bruce McCall’s Zany Afternoons” (1982), “The Last Dream-o-Rama: The Cars Detroit Forgot to Build, 1950-1960” (2001), and “All Meat Looks Like South America: The World of Bruce McCall” (2003).

Bruce Paul Gordon McCall was born on May 10, 1935, in Simcoe, Ontario, to Thomas Cameron and Helen Margaret (Gilbertson) McCall.

His father, who was known as T.C., was a civil servant and later Chrysler’s public relations manager in Canada. His mother was a homemaker.

Bruce grew up with five siblings in a home tightly circumscribed by T.C.’s paltry salary and the dour provincialism of Simcoe, in the southwest corner of the province, not far from Lake Erie.

Bruce grew up with five siblings in a home tightly circumscribed by T.C.’s paltry salary and the dour provincialism of Simcoe, in the southwest corner of the province, not far from Lake Erie.

This childhood purgatory provided the material for his 1997 memoir, “Thin Ice: Coming of Age in Canada.”

A second memoir, “How Did I Get Here?,” was published in 2020.

It showed, on a supposedly dissolute strip, derelicts swigging maple syrup and louche emporiums promising such forbidden pleasures as “live, hatless girls.”

American popular culture sparked his imagination, especially the magazines and their advertising, which transmitted “messages of tomorrow in steel and chrome,” he wrote in “Thin Ice.”

“Soon, double-decker Boeing Stratocruisers with cocktail lounges would be flying down to Rio in 20 hours,” he added. “Standard transportation for Everyman was about to be a car you could fly, a plane you could drive.”

American popular culture sparked his imagination, especially the magazines and their advertising, which transmitted “messages of tomorrow in steel and chrome,” he wrote in “Thin Ice.”

“Soon, double-decker Boeing Stratocruisers with cocktail lounges would be flying down to Rio in 20 hours,” he added. “Standard transportation for Everyman was about to be a car you could fly, a plane you could drive.”

“The Detroit products at the time — those behemoths — were so awful that I found them funny and ridiculous,” he told The New Yorker in 2002. “So the roots of satire were planted very early.”

He was hired in 1959 by A.V. Roe & Company in Toronto to retouch photos of pots and pans for its catalogs.

He was hired in 1959 by A.V. Roe & Company in Toronto to retouch photos of pots and pans for its catalogs.

A year later his fortunes improved, marginally, when the publishing company Maclean-Hunter hired him to churn out brief articles for trade magazines like Pit & Quarry. He loathed the job.

In desperation, Mr. McCall, a sports car enthusiast, collaborated with a friend to start a magazine, Canadian Driver.

It lasted only one issue, but it led to a writing job at Canada Track & Traffic, where Mr. McCall soon became editor in chief.

His first crack at the American dream came in 1962, when David E. Davis, the head of the Campbell-Ewald agency in Detroit, which had Chevrolet as a major account, hired him to write ad copy for Corvettes and Corvairs.

His first crack at the American dream came in 1962, when David E. Davis, the head of the Campbell-Ewald agency in Detroit, which had Chevrolet as a major account, hired him to write ad copy for Corvettes and Corvairs.

It was the springboard to a flourishing career in New York, where he initially worked on Ford advertising at J. Walter Thompson.

Later, at Ogilvy & Mather, Mr. McCall was put in charge of advertising for Mercedes-Benz; for several years he ran the agency’s Frankfurt office.

In 1970, Mr. McCall and his friend Brock Yates, the editor of Car and Driver, invented a series of mythical airplanes, among them the Humbley-Pudge Gallipoli Heavyish Bomber, for which they wrote pseudo-scholarly historical notes.

Playboy bought the idea, assigned Mr. McCall to do the illustrations and ran the collaboration in January 1971 under the title “Major Howdy Bixby’s Album of Forgotten Warbirds.”

It went on to win Playboy’s annual humor award.

“This went to my head — in fact rearranged its contents,” Mr. McCall told Macmillan in an interview for its website in 2008.

“This went to my head — in fact rearranged its contents,” Mr. McCall told Macmillan in an interview for its website in 2008.

“On the basis of that one fluke success, I now felt entitled to see myself as a working professional humorist.”

After returning from Germany, he headed for the offices of National Lampoon with a catalog for the mythical 1958 Bulgemobile.

After returning from Germany, he headed for the offices of National Lampoon with a catalog for the mythical 1958 Bulgemobile.

The magazine offered him a contract to illustrate 25 pages a year.

He was soon delivering spreads on the luxury liner Tyrannic (“So safe that she carries no insurance”) and blue-blood sports like tank polo and zeppelin shooting.

“Popular Workbench,” a series based on his large collection of 1930s popular science magazines, offered such innovations as a 4,000-horsepower diesel typewriter weighing more than three tons.

McCall wrote for “The National Lampoon Radio Hour” and put in a brief, unhappy stint as a writer for “Saturday Night Live” in the late 1970s before returning to advertising.

He joined the McCaffrey & McCall agency (co-founded by an unrelated McCall), which had just landed the Mercedes account.

After several years as creative director for Mercedes advertising, he was named executive vice president and creative director of the agency. He left in 1993.

By then his career as a writer and illustrator had taken off.

By then his career as a writer and illustrator had taken off.

Infatuated with The New Yorker since childhood, Mr. McCall submitted a humor article for the magazine’s “Shouts and Murmurs” department in 1980, the first of more than 80 to be published over the next 40 years.

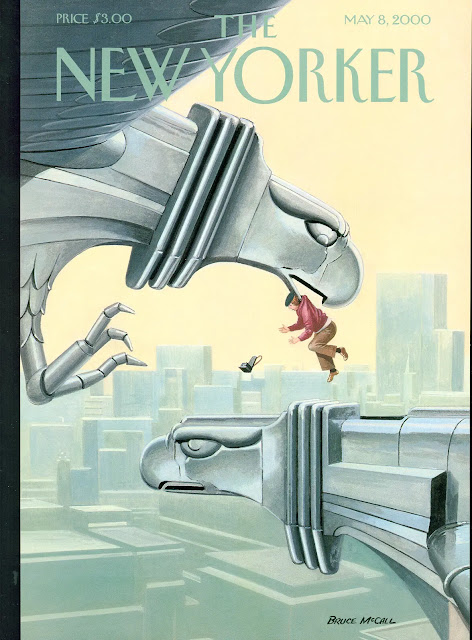

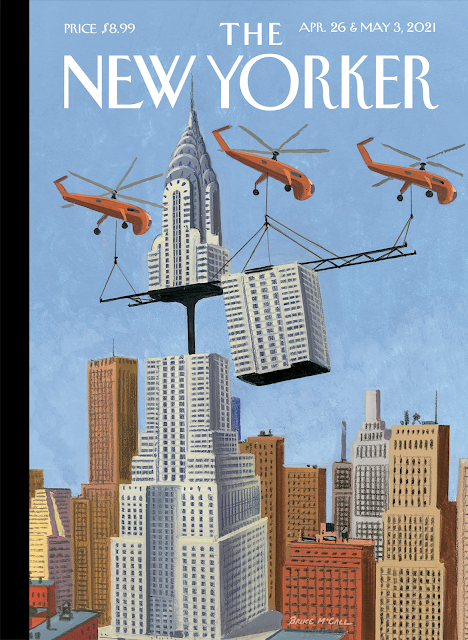

After Tina Brown became editor in 1992, his illustrations appeared regularly on the magazine’s cover and in the back of the book.

|

"The Ascent of Man", The New Yorker, May14, 2007. |

He had long worked from his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by their daughter, Amanda McCall; two brothers, Walter and Michael; and a sister, Christine Jerome.

Mr. McCall wrote the children’s book “Marveltown” (2008) and provided the illustrations for “The Steps Across the Water,” a 2010 children’s book by the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik.

He went on to collaborate with David Letterman in 2013 on a lavishly illustrated skewering of the American superrich, “This Land Was Made for You and Me (But Mostly Me): Billionaires in the Wild.”

Read also:

"Remembering Bruce McCall, Satirist and Compleat Canadian" in The New Yorker.

No comments:

Post a Comment