From The Washington Post.

The cause was congestive heart failure, said his wife, JZ Holden.

Mr. Feiffer’s weekly comic strip “Feiffer” — initially called “Sick, Sick, Sick” — ran in the Village Voice from 1956 to 2000 and was syndicated to more than 100 newspapers.

In an era defined by the nuclear bomb, the Cold War, racial tensions and the sexual revolution, Mr. Feiffer added his nerve-racked perspective to an influential cultural stage occupied by humorists such as Woody Allen, Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce and the team of Mike Nichols and Elaine May.

Mr. Feiffer found his voice in comics that provided a sardonic and sarcastic takedown of authority and conventional wisdom.

In addition, he told the Los Angeles Times, his work explored “how people use language not to communicate, and the use of power in relationships.”

“No other cartoon in strip format was dealing on a regular basis with themes as adult as sex, politics, psychiatry,” Trudeau once said.

Mr. Feiffer’s characters brimmed with self-pity and self-absorption. They were, in their creator’s words, “so busy explaining themselves that they never shut up.”

He won the Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning in 1986.

Unapologetically liberal in his political views, Mr. Feiffer was one of the first cartoonists to criticize the Vietnam War in a mainstream newspaper.

In his 2010 memoir, “Backing Into Forward,” he credited his mother with inadvertently sharpening his political sensibilities.

Referring to the secretary of defense during the Vietnam War, Mr. Feiffer wrote, “The McNamara explanation — ‘We have access to information that you don’t have’ — reminded me of my mother’s answer when I asked her to give me a reason for an action or decision she couldn’t be bothered to explain or defend.

The reason she gave that ended all discussion was ‘Because.’

“My government was, in a sense, telling me ‘Because.’ And it made me every bit as outraged as I was at eight or nine.”

“My government was, in a sense, telling me ‘Because.’ And it made me every bit as outraged as I was at eight or nine.”

“Munro,” his best-selling 1959 book about a 4-year-old boy who is mistakenly drafted into the Army, became an Academy Award-winning animated short film in 1961, with a script by Mr. Feiffer.

His best-known screenplay was “Carnal Knowledge,” the 1971 film directed by Nichols that follows the sexual exploits of two men from their lusty college years in the 1940s to their misogynistic middle age amid the sexual revolution.

Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel played the two friends who are unable to connect — first emotionally, then physically — with women.

The film, which co-starred Ann-Margret (who received an Oscar nomination) and Candice Bergen, caused a sensation for its sexual frankness.

A Georgia theater manager was arrested and convicted for showing the movie after it was found to be obscene under state law.

The film, which co-starred Ann-Margret (who received an Oscar nomination) and Candice Bergen, caused a sensation for its sexual frankness.

A Georgia theater manager was arrested and convicted for showing the movie after it was found to be obscene under state law.

The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled against the Georgia Supreme Court in the matter, finding “Carnal Knowledge” did not depict sexual conduct in a “patently offensive” way.

In the New York Times, film reviewer Vincent Canby called the movie “a series of slightly mad dialogues between two people … that almost always lead to new plateaus of psychic misunderstanding and emotional hurt.”

The film, Canby added, “is merciless toward both its men and its women in order to reach some kind of understanding of them, of their capacities for self-delusion and for the casual infliction of pain.”

The film’s two male characters were based on characters from “Feiffer”: the cartoonist’s insecure alter ego, Bernard Mergendeiler, and his sexually confident friend Huey.

“It’s after midnight and she’s going to see me!” Bernard exclaims to Huey in a 1957 panel, adding worriedly: “How can you have any respect for someone like that?”

The film’s two male characters were based on characters from “Feiffer”: the cartoonist’s insecure alter ego, Bernard Mergendeiler, and his sexually confident friend Huey.

“It’s after midnight and she’s going to see me!” Bernard exclaims to Huey in a 1957 panel, adding worriedly: “How can you have any respect for someone like that?”

Arguing politics

Jules Ralph Feiffer, whose parents were Jewish immigrants from Poland, was born in the Bronx on Jan. 26, 1929. He was the middle of three children and the only son.

His taciturn father was a salesman who had little luck during the Depression.

Mr. Feiffer described his mother, who supported the family selling fashion drawings to department stores, as an unaffectionate woman who dominated the household and “placed all her hopes and dreams on me.”

Gawky and timid as a child, Mr. Feiffer passed the time drawing and arguing politics with his older sister, Mimi, a party-line communist.

Gawky and timid as a child, Mr. Feiffer passed the time drawing and arguing politics with his older sister, Mimi, a party-line communist.

(At the other end of the spectrum was Mr. Feiffer’s distant cousin Roy Cohn, chief counsel to Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy during the anti-communist witch hunts of the 1950s and the relative held up to Mr. Feiffer as a role model by one of his aunts.)

Growing up, Mr. Feiffer adored the comics of Will Eisner, creator of “The Spirit,” a popular crime-fighting strip.

Growing up, Mr. Feiffer adored the comics of Will Eisner, creator of “The Spirit,” a popular crime-fighting strip.

As a teen, Mr. Feiffer talked his way into apprenticing under Eisner for no pay. “Eisner found me useless as an artist, but he liked the way I wrote,” he later told the New Yorker.

Soon, Mr. Feiffer was writing entire episodes of “The Spirit” and drawing a back-page strip called “Clifford,” about the adventures of a little boy.

“The Army made a satirist out of me,” he later said. From the moment he was drafted in 1951, he began concocting a plan to fake a nervous breakdown to escape possible combat duty in Korea. Ultimately, he said he spent much of his time decorating helmets for the officers.

Discharged in 1953, Mr. Feiffer was unable to get his comic work published. He worked at various jobs, getting himself fired every six months so he could collect unemployment. He called it “my own personal National Endowment for the Arts subsidy, awarded by myself at six-month intervals for a period of three years.”

In 1956, he approached the Village Voice, a new weekly paper he had seen in the offices of the publishers who had been rejecting him, and offered to do a comic. He received no pay for it for the first eight years.

Mr. Feiffer originally called the strip “Sick, Sick, Sick” but changed the title to “Feiffer,” fearing that readers might think it was his humor that was sick and not society.

His depictions of garrulous neurotics struck a chord, and collections of his cartoons — starting with “Sick, Sick, Sick: A Guide to Non-Confident Living” (1958) — became bestsellers.

Hugh Hefner, a Feiffer fan, put the cartoonist on retainer at his magazine, Playboy.

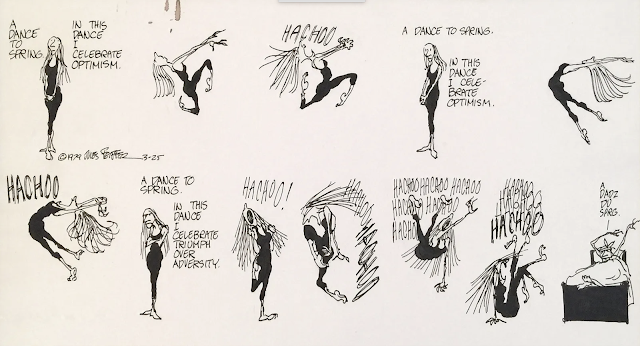

Recurring “Feiffer” characters included the moody young woman in a black leotard who danced to the seasons or the new year, often to end up somehow thwarted: covered in a sudden snowfall or clutching a pistol in self-defense against the coming year.

He told the New York Times the dancer was based on “the first girl who ever slept with me and spent the night.”

His marriages to Judy Sheftel and Jennifer Allen ended in divorce.

His marriages to Judy Sheftel and Jennifer Allen ended in divorce.

In 2016, he wed Holden, a writer.

In addition to his wife, survivors include a daughter from his first marriage, Kate Feiffer, who collaborated with her father on several children’s books; two daughters from his second marriage, actress Halley Feiffer and Julie Feiffer; and two granddaughters.

Mr. Feiffer was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995. He received the National Cartoonists Society’s Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.

Mr. Feiffer was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1995. He received the National Cartoonists Society’s Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.

Besides his strip “Feiffer,” Mr. Feiffer’s other work included the comic “Boom!” (1958), an early satire of the nuclear arms race.

He also wrote what he called “novels-in-cartoons,” proto-graphic novels that heralded the blossoming of long-form comics such as Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and Chris Ware’s “Jimmy Corrigan.”

They included “Passionella, and Other Stories” (1959) and “Tantrum” (1979), the latter the story of a 42-year-old man who throws a fit that transforms him back into a toddler.

Mr. Feiffer’s movie scripts included a live-action version of “Popeye” (1980), starring Robin Williams in prosthetic forearms.

Mr. Feiffer’s movie scripts included a live-action version of “Popeye” (1980), starring Robin Williams in prosthetic forearms.

Expensively filmed on an elaborate set in Malta, the movie — which culminated in Popeye’s fistfight with a giant octopus — was widely panned.

Working in theater, Mr. Feiffer contributed sketches — along with Kenneth Tynan, Samuel Beckett, John Lennon, Sam Shepard and Edna O’Brien — to the long-running, critically reviled erotic musical revue “Oh! Calcutta!,” which debuted in 1969.

Mr. Feiffer’s “Little Murders” (1967), a response to the John F. Kennedy assassination that depicts an urban America awash in random violence, closed on Broadway within a week.

Working in theater, Mr. Feiffer contributed sketches — along with Kenneth Tynan, Samuel Beckett, John Lennon, Sam Shepard and Edna O’Brien — to the long-running, critically reviled erotic musical revue “Oh! Calcutta!,” which debuted in 1969.

Mr. Feiffer’s “Little Murders” (1967), a response to the John F. Kennedy assassination that depicts an urban America awash in random violence, closed on Broadway within a week.

Revived successfully in London and then off-Broadway, it won an Obie Award and became a film in 1971 starring Elliott Gould.

His other plays included “Grown Ups” (1981), about a middle-aged New York Times reporter who can never quite live up to his Jewish parents’ expectations.

“Mr. Feiffer takes the most familiar tribal greetings — ‘So what’s new?’ or ‘When am I going to see my granddaughter?’ — and forces us to see the resentments and hurts that fester underneath,” theater critic Frank Rich wrote in the New York Times.

His other plays included “Grown Ups” (1981), about a middle-aged New York Times reporter who can never quite live up to his Jewish parents’ expectations.

“Mr. Feiffer takes the most familiar tribal greetings — ‘So what’s new?’ or ‘When am I going to see my granddaughter?’ — and forces us to see the resentments and hurts that fester underneath,” theater critic Frank Rich wrote in the New York Times.

“It’s when we see the gap that separates such lines from the truth that our laughter curdles.”

As “Feiffer” wound down, the cartoonist — who in 1961 illustrated the now-classic children’s novel “The Phantom Tollbooth” by his friend Norton Juster — successfully reinvented himself as a children’s book author and illustrator.

As “Feiffer” wound down, the cartoonist — who in 1961 illustrated the now-classic children’s novel “The Phantom Tollbooth” by his friend Norton Juster — successfully reinvented himself as a children’s book author and illustrator.

“Bark, George” (1999) features a Feifferean puppy who is unable to communicate as commanded by his long-suffering mother.

Surveying his long, varied career, Mr. Feiffer wrote in his memoir that it took a new turn each time he was “backed into a corner,” rather than as a result of any conscious planning.

“It’s a good thing I had no direction,” he concluded. “I might have given up.”

Read also:

- "My Friend Jules Feiffer", Edward Sorel in The Atlantic.

- "Eyeball Kicks: Jules Feiffer's Glory Years", Françoise Mouly in The New Yorker.

- Collectors on Collecting: Jules Feiffer on the Artists and Works from His Collection.

- "The Old Soft Shoe" by R.C. Harvey.

- Kjell Knudde’s entry for Feiffer at Lambiek’s Comiclopedia.

No comments:

Post a Comment